CNN’s national security analyst Peter Bergen just wrote that attacks such as the one in Buffalo can be prevented. Yes, they can. Not always, but often.

However, this requires a lot more than the six steps Peter Bergen offers in his article. Bergen is not only CNN’s national security analyst, a vice president at New America (a think tank) and a professor of practice at Arizona State University.

What is a professor of practice?

Bergen begins by making a terrible mistake by calling this “a very American tale of domestic terrorism”, ignoring victims of similar attacks all over the world. A dreadful shooting in New Zealand, a horrible attack in Norway and a recent tragic incident in Plymouth in England come to mind as first examples. Also in Asia and Africa there have been many of these incidents, but they likely come about differently, though I can’t be sure of that.

First, “let’s stop naming the terrorists,” Peter Bergen continues. He writes that “these misguided individuals are typically zeros trying to be heroes”. Not only is this a useless suggestion because even if journalists were to refrain from naming these people, many more others still do and they would do so even more to counter that silence. Crucially, however, Bergen completely misses that this – feeling like zeros – is often exactly what is at the root of these incidents. I find it hard to believe that he completely overlooks the significance of what he is saying.

A great deal of this violence stems from the fact that so many youngsters – and not just youngsters – feel that their lives have no significance and are overwhelmed by feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness, not to mention sheer boredom.

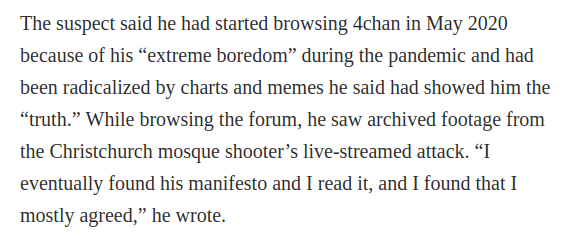

Second, Bergen mentions social media, and argues for the removal of content that encourages violence. This overlooks that this kind of content does not only pop up on regular social media, but still more often in the dark nooks and crannies of the internet. This also overlooks that if you ban content, you may merely be pushing it underground where it can’t be monitored. He does not even mention 4chan. That said, I agree that it is important to police fake news and fake science as any otherizing language lowers the threshold toward violence, neuroscience teaches us.

After the 2011 riots in England, some of the participants indicated that boredom had been an important driver and that merely providing access to sports facilities can help prevent such escalations.

Leaders who want to learn about how big a role boredom plays should watch the video about the “Philmarillion”, a person who for months documented every move and twitch of a particular online user based in England. This person created an entire world made up of the posts of said user, and even engaged in performance art to simulate that said user was living with him.

We should be grateful that the Philmarillion was artistically inclined.

Can you see what boredom can do to others, who have nowhere else to be and to go and no outlet for whatever ails them?

As a third step towards preventing shootings like the one in Buffalo, Peter Bergen mentions the discipline of threat management. He explains that suspects often follow a predictable path to violence, but that still does not identify them to us and does not enable us to interfere. The article does mention that the FBI has recently doubled the number of people who work on domestic terrorism and extremism, but that reflects the developments rather than predates them.

As a fourth step, Bergen mentions that “officials” need a better understanding of the concept of “leakage,” that peers usually have “the most useful information about attack planning, but were the least likely to come forward with relevant information to law enforcement”.

He then makes the following nonsensical statement:

How do you investigate a “potential act of terrorism”? Because that’s like potentially winning the lottery. You can’t investigate something that does not exist or has not happened. I think what he means is that if school officials etc are concerned about a student, law enforcement should talk with the student’s friends and take them seriously.

As the fifth step, he mentions an American policy that sounds like the UK counterpart called “Prevent”. Logos of pro-cycling and pro-wildlife activists are examples of what UK school teachers need to be on the lookout for and report. If the US policy is anything like Prevent, all we end up with is more distrust in society instead of less.

As sixth and final step, Bergen kicks against an open door by stating that kids like this shooter should never have been able to purchase his weaponry. That is certainly true, but the Plymouth shooter – in England, where guns are not a birthright, unlike in the US – not only had a shotgun, it had been confiscated yet returned to him shortly before the incident.

There currently seems to be a large number of mostly young white males out there who feel indeed, as Peter Bergen puts it, like zeros. They often feel disenfranchised, whether it is about their perceived right to have sex with any woman or another issue, but something happens right before this starts to fester and they go online, looking for echo chambers in which they finally feel heard and understood.

Guys like Payton Gendron are not that different from guys like Jake Davison.

They need people to blame, to direct their powerlessness at, whether it is non-whites in general or a particular group of people in particular, or Jews or women or immigrants.

(Women too are sometimes part of these movements, though.)

The question to ask is:

How do these youngsters end up in these online and offline echo chambers filled with hate? What happens before they go there?

The problem is that they’re still too young to monitor themselves, recognize what is happening to them, stop themselves in time and turn away, surround themselves with positivity instead. Echo chambers come in all kinds.

Apparently, it was particularly types like Bannon and Trump who have very deliberately been targeting these dark places on the internet, who whip up this hate, to make people feel that something has been taken from them that should be theirs and that it’s the Trumps of the world who will get it back for them. Divide people, promise to defend them against the “enemy” and get their votes.

Maybe it’s politicians and their close associates, then, who should all begin to be monitored to prevent potential acts of domestic terrorism?

They may be the ones who sow the seeds for this hate.

They certainly should be monitored for otherizing language and be called out on it, be made aware of how dangerous that is, if they don’t know that yet.

Where are things going wrong for these youngsters, people like Payton Gendron? At what age does this start? Around 10 or 12 or perhaps even earlier? They are often still as young as 14 when they end up on these forums where they become radicalized. What exactly is it that goes wrong in their lives?

(It certainly does not match Tony Blair’s old theories about “hooligans” and graffiti artists. Payton Gendron’s parents are two happy-looking civil engineers.)

WHY do these kids feel like fat zeros?

WHY?

Payton Gendron had just started college. The pandemic probably cut it short. He went to 4chan because he was bored. Could it really be only boredom that drives young people to these places of hate?? Boredom does make angry. Boredom does lead to a buildup of energy.

What was Payton Gendron like before he started hanging out on 4chan?