Update 26 April 2024: https://nos.nl/artikel/2518221-tweede-kamer-wil-toch-bestrijdingsmiddel-voor-door-fruitvlieg-geplaagde-kersen (So maybe these Dutch cherry growers will get to help pollute the world a little bit more after all as maybe these insecticides are allowed in Germany after all? The panic over not being able to use them seems exaggerated if I look at what that Wageningen University experiment found. These cherry growers need to stick to a best practice approach. They also failed to do that when they were granted an exemption for these pesticides and ignored the conditions for their use, which is why the Dutch state pulled the exemption.)

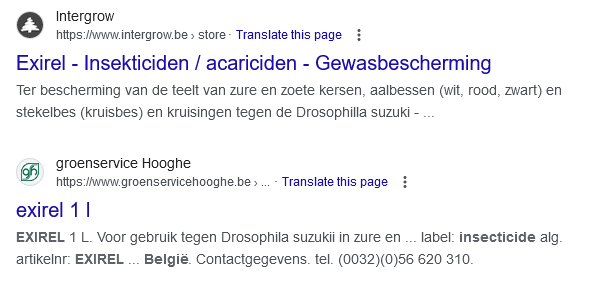

This morning at 04:45 BST, the Dutch version of the BBC – it’s called NOS – published an article in which Dutch cherry growers lament about no longer being allowed to use the insecticides Tracer and Exirel to combat Drosophila suzukii.

Drosophila suzukii aka spotted wing drosophila is a fruit fly that originated in Asia and of which the females lay eggs in ripening fruits, such as berries, grapes, plums and cherries. It was first spotted in the Netherlands in 2012.

It likely arrived in Europe in imported fruit, according to this study: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6681294/ (It also talks about the use of cladding and netting to combat this fruit fly. I’ll come back to that.)

Dutch cherry growers had an exemption that allowed them to use Exirel and Tracer, but because they weren’t keeping their side of the agreement, the Dutch government canceled the exemption. It wants to improve water quality instead of worsen it and it does not want to cause more harm to bees. The cherry growers weren’t cooperating.

First, let’s look into these two pesticides. Why are they problematic?

Exirel

When I went to PubMed and typed in “Exirel”, the first thing that popped up was an intriguing title about dodgy claims but that refers to an asthma medication, a bronchodilator called pirbuterol.

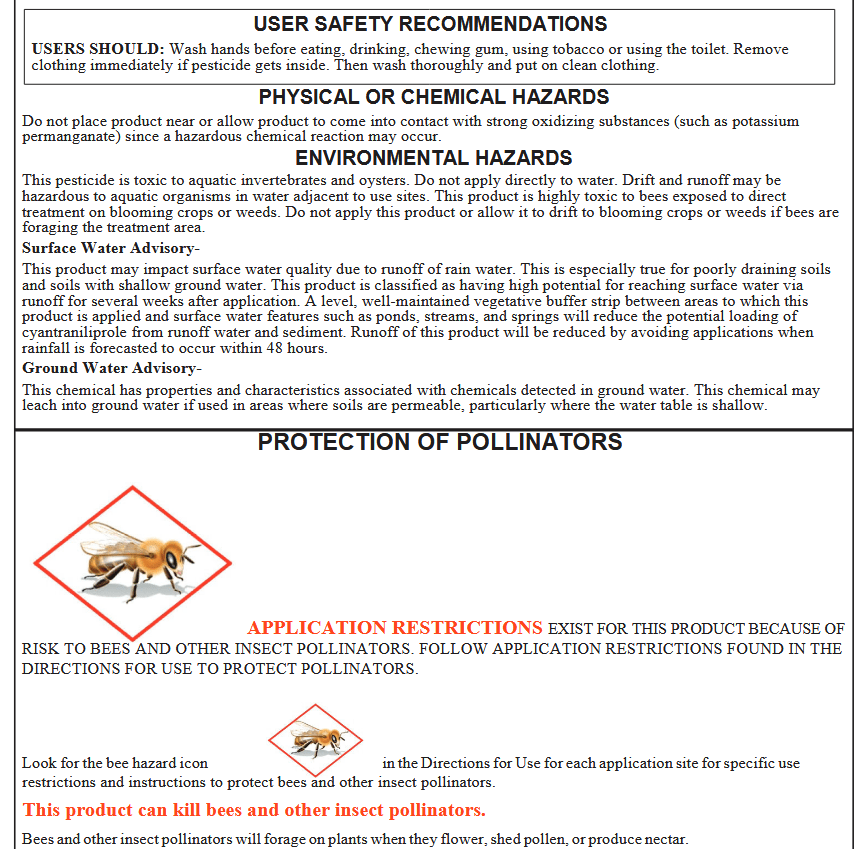

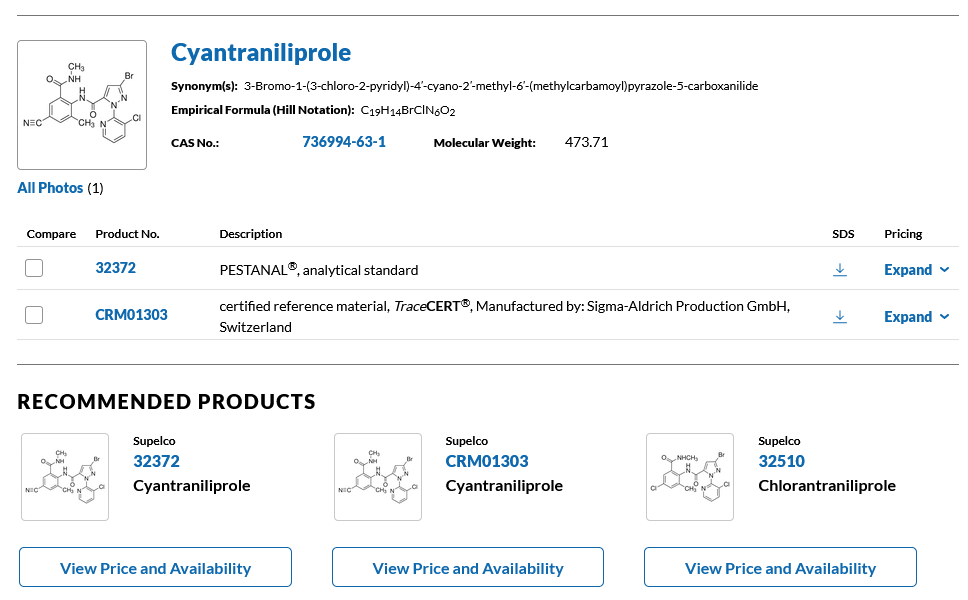

The insecticide Exirel, that’s cyantraniliprole. The EPA calls it a “broad-spectrum” (hence not specifically targeted at Drosophila suzukii) insecticide for controlling insects with mandibulate as well as piercing-sucking mouthparts.

It is supposed to get into the leaves as it works best when insects ingest parts of leaves.

Source: https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/ppls/000279-09615-20190611.pdf

The problem?

IT IS HIGHLY TOXIC TO BEES, TOO, AS WELL AS TO OYSTERS AND AQUATIC INVERTEBRATES SUCH AS SHRIMP. And it’s new, which means that not enough may be known about it yet.

There you have it. I don’t need to look any further regarding why Exirel use should be restricted as much as possible. When I typed “cyantraniliprole ” into PubMed, however, one study this popped up found that it induces oxidative stress and thereby affects reproduction in certain rats. Rats are mammals, just like humans.

The following article also got my attention.

Abstract

As a representative variety of diamide insecticides, cyantraniliprole has broad application prospects. In this study, the fate and risk of cyantraniliprole and its main metabolite J9Z38 in a water-sediment system were investigated. The present result showed that more J9Z38 was adsorbed in the sediment at the end of exposure. However, the bioaccumulation capacity of cyantraniliprole in zebrafish was higher than that of J9Z38. Cyantraniliprole had stronger influence on the antioxidant system and detoxification system of zebrafish than J9Z38. Moreover, cyantraniliprole induced more significant oxidative stress effect and more differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in zebrafish. Cyantraniliprole had significantly influence on the expression of RyR-receptor-related genes, which was confirmed by resolving their binding modes with key receptor proteins using AlphaFold2 and molecular docking techniques. In the sediment, both cyantraniliprole and J9Z38 had inhibitory effects on microbial community structure diversity and metabolic function, especially cyantraniliprole. The methane metabolism pathway, mediated by methanogens such as Methanolinea, Methanoregula, and Methanosaeta, may be the main pathway of degradation of cyantraniliprole and J9Z38 in sediments. The present results demonstrated that metabolism can reduce the environmental risk of cyantraniliprole in water-sediment system to a certain extent.

MY COMMENT, for now: Methanogens produce methane, a greenhouse gas.

See that this matter is not as straightforward as cherry growers may think it is? Don’t they need the bees, too, for starters?

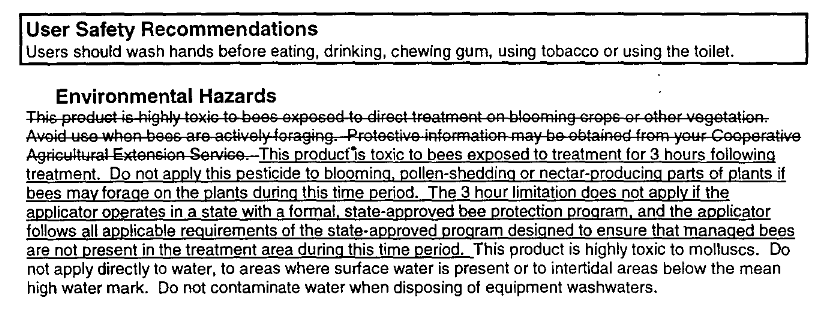

TRACER

Next, I did a search on “tracer insecticide” in PubMed. As anticipated, that turned up nothing because of the highly generic brand name. (Why use such a generic brand name?) A web search turned up sponsored results. It is a suspension concentrate containing 480 g/liter (44.03% w/w) of spinosad. That is a selective (not broad-spectrum) insecticide for use in top fruit etc.

This is what the EPA has on it: https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/ppls/062719-00267-20010619.pdf (documented dated year 2001)

So Tracer (Naturalyte, spinosad) has similar problems as Exirel (cyantraniliprole), and as it affects bees too, it may not really be that selective, but its toxicity is lower. It is fermentation-derived and is also used in for example the treatment of head lice on humans: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=spinosad

A slightly more recent EPA file (dated year 2008), does not really appear to contain anything new with regard to toxicity: https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/ppls/062719-00267-20080814.pdf

CAN TRACER AND EXIREL BE FREELY USED IN GERMANY AND BELGIUM?

That’s what Dutch cherry growers claim in the NOS article. I don’t think that this is very easy for me to verify, but I gave it a shot and found this:

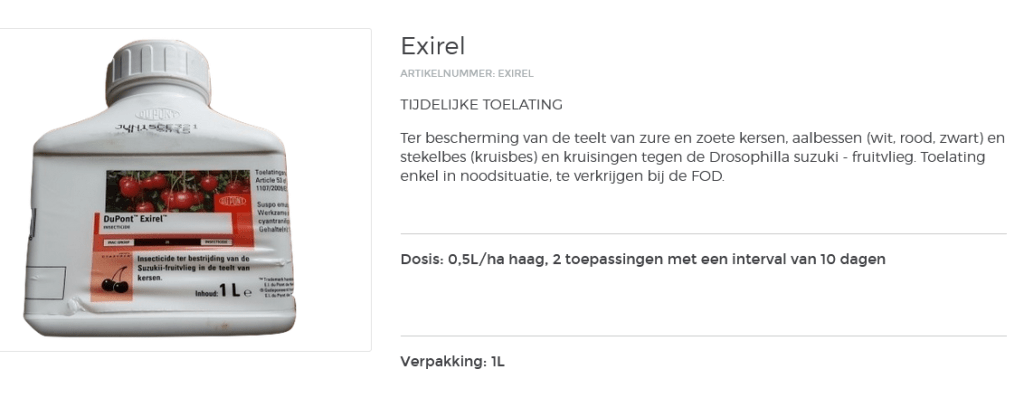

I clicked on the first link and found this:

In other words, Exirel cannot be freely used in Belgium either, if I can trust the information on that website. An emergency exemption can be applied for, it says.

The second link yielded this:

Clicking on the links on that second website caused my browser to give off safety warnings about wanting to proceed to a URL that wasn’t what it was supposed to be, and so I did not proceed.

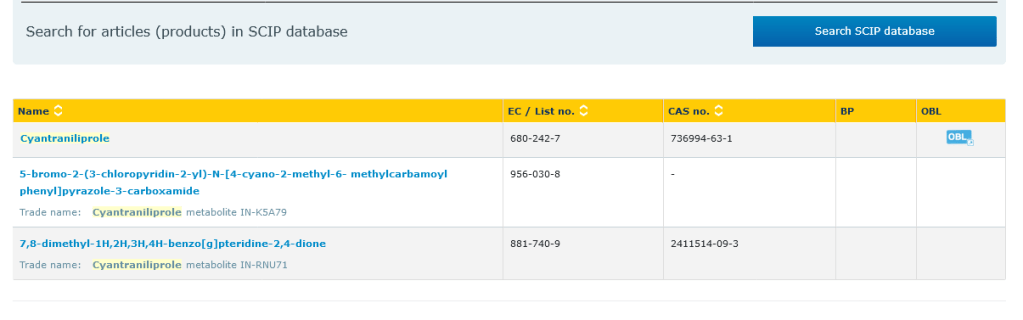

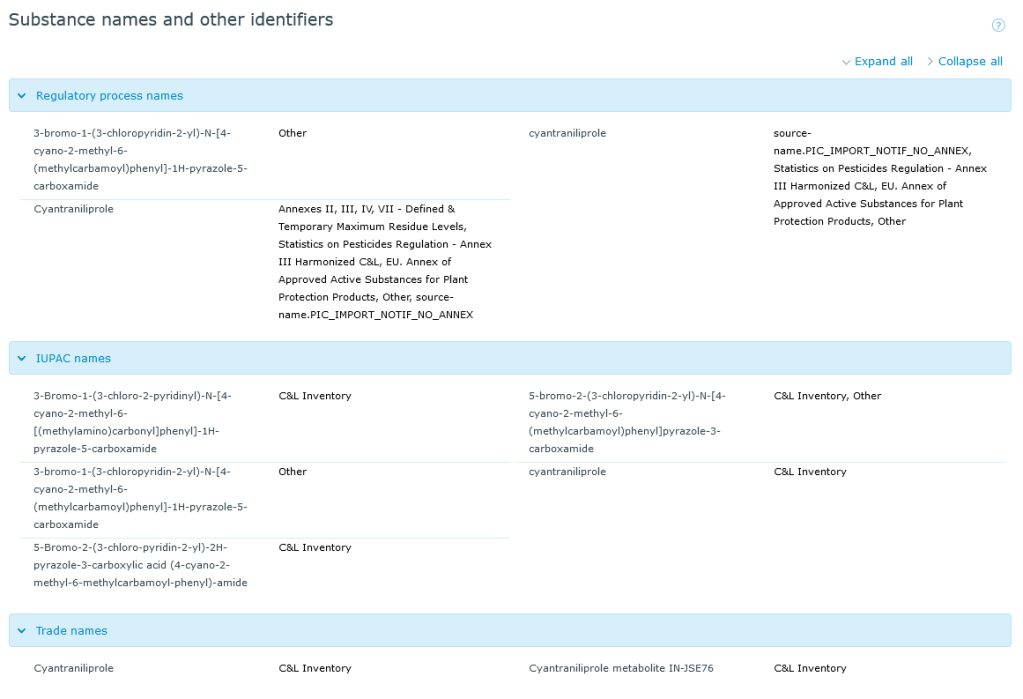

Then I went to the EU chemicals database:

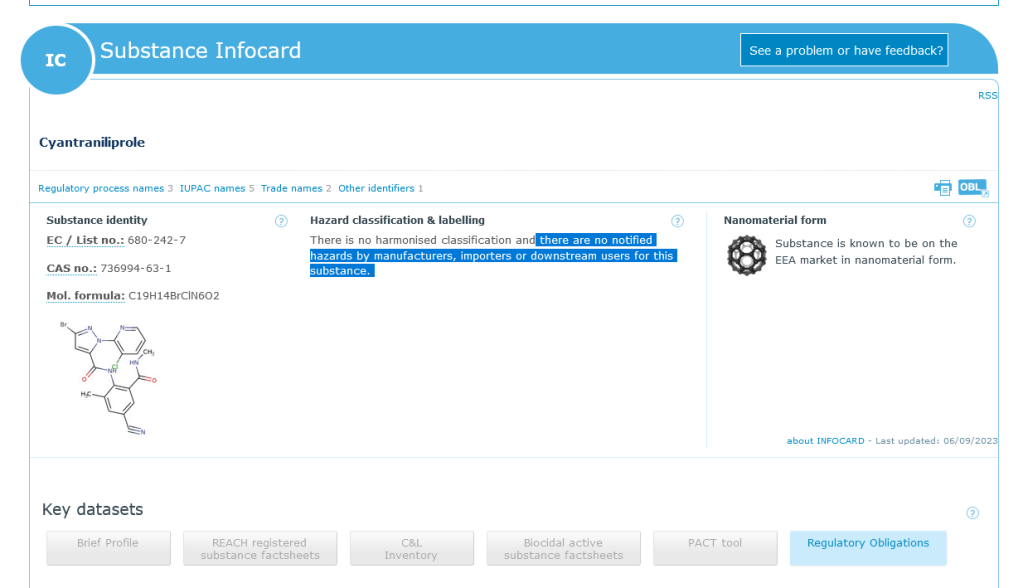

When I clicked on the link on the left, I learned that this is a nanomaterial: https://echa.europa.eu/substance-information/-/substanceinfo/100.205.162 It says “there are no notified hazards by manufacturers, importers or downstream users for this substance” but we’ve already learned from the EPA documentation that this does not mean that there are no hazards.

DuPont (which has merged with Dow, I think?) is not the only one who produces it.

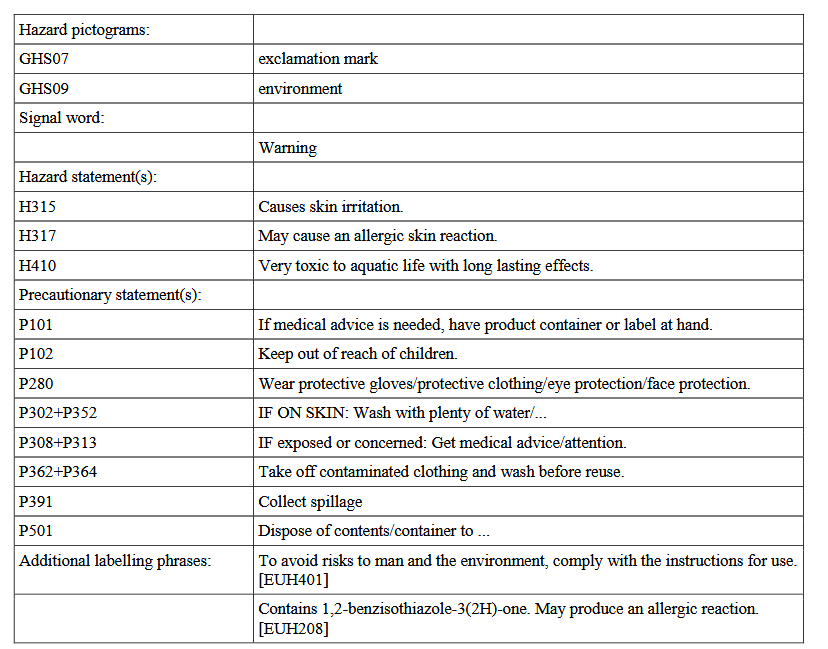

SDS: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/NL/en/sds/sial/32372

From that Safety Data Sheet:

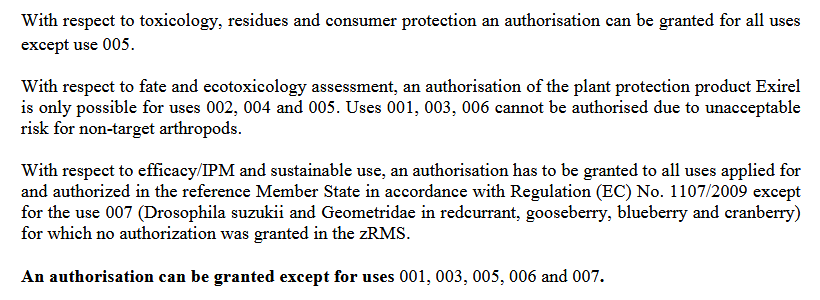

For Germany, I found this: https://www.bvl.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/04_Pflanzenschutzmittel/01_zulassungsberichte/00A670-00-00.pdf

Use 001 =

Use 002 (allowed) = sweet cherry for tortrix moth (Tortricidae) (TORTRC), Geometridae (GEOMER)

Use 003 = sweet cherry for the purpose of eradicating Drosophila suzukii

USE 004 = grape vine

Use 005 =

Use 006 =

Use 007 = includes the purpose of eradicating Drosophila suzukii

So if this information is accurate and current, and why wouldn’t it be, this would also contradict what the cherry grower said about Exirel use in Germany. The document does not mention tart cherries, however.

ALTERNATIVES

I think you get the picture. Certainly Exirel, also when sold under different brand names, is quite toxic and Exirel is relatively new.

Cladding and netting were mentioned in the study I linked at the top of this page, but I had already spotted some webpages by one of the world’s top agricultural universities before I started writing this post. Let’s go there next.

- https://www.wur.nl/en/article/suzuki-fruitfly.htm : “What can fruit growers do to cope with Drosophila Suzukii? Good hygiene during the growing season is very important. By frequently and thoroughly harvesting ripe fruit and removing and destroying rotting fruit, the development of new generations of fruit flies can be prevented.”

Why not use nature-minded volunteers to help with this, particularly with the removal of rotting fruit? They also lay eggs in undamaged fruit but of course, they’ll particularly go for easy targets, I imagine.

Infected fruits are recognizable with a magnifying glass.

The Dutch version of this page mentions that netting can help as well. It would have to be very-fine mesh to keep insects out. That would mean that wildlife such as birds wouldn’t get caught in it.

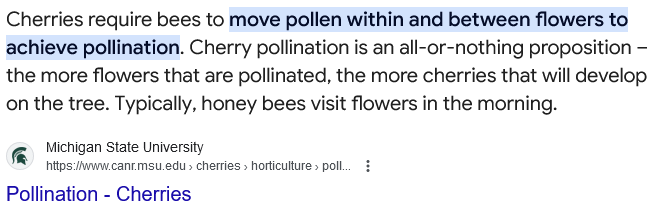

QUESTION: As bees would need early access, I imagine, the timing of installing the netting is crucial? (Or are bees kept inside of the netting? Hives?)

Yes, bees need access:

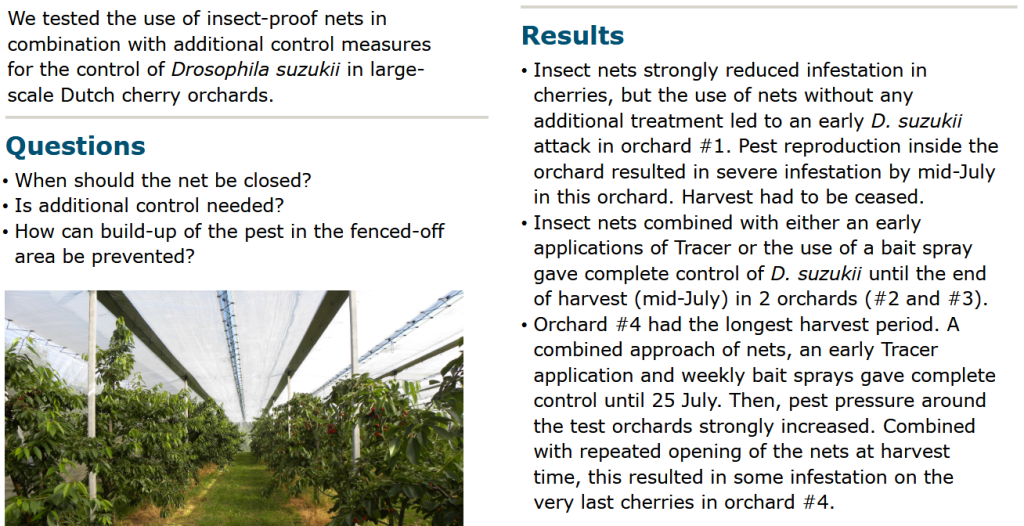

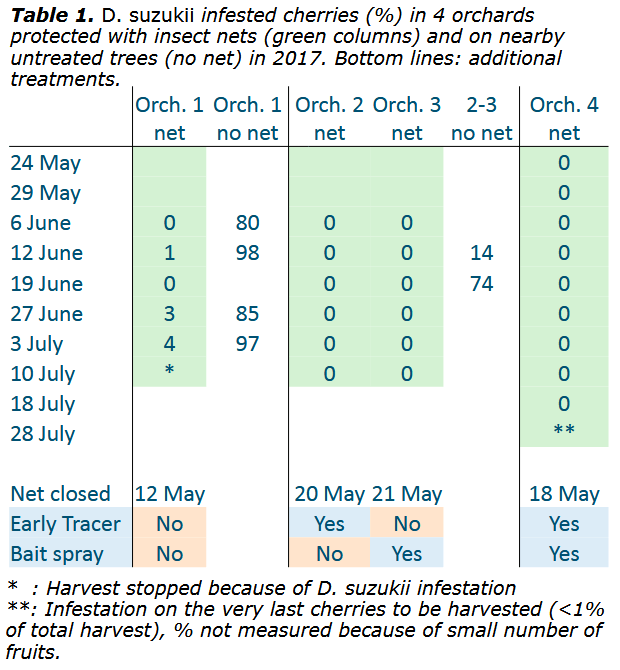

As you can see, there are marked differences between these orchards. Use of netting only led to problems in only 1 of the 4 commercial orchards that participated in these tests. You can also see that having a long harvest period seems to increase the probability of an infestation. This appears to indicate that management is key, not insecticide use. Of course, 4 is a very low sample number to be able to draw definite conclusions from, but these results are interesting.

Let’s go back to that first link now: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6681294/

Combinations of cladding, netting and insecticides were used in that English study.

Here is are two interesting bits:

“Within their field trial, Shawer et al. [41] failed to prevent fruit damage with the insecticide programs. However, this was attributed to high pest pressure prior to the start of the program [41]. This stresses the importance of implementing D. suzukii control strategies early in the growing season to prevent population growth prior to the appearance of fruit.“

“The initial investment required to deploy insect mesh is high [8], however the long life span of the equipment (expected to be between 7–10 years) results in a physical barrier against D. suzukii that can be used for subsequent seasons. This initial cost is also likely to be offset by savings in the use of plant protection products but also labor costs and the handling and disposal of waste fruit. This system has also been highly effective in reducing the immigration of pest numbers including Halyomorpha halys Stål (brown marmorated stinkbug), Cydia pomonella (Linnaeus) (codling moth), and Grapholita molesta (Busck) (oriental fruit moth) into crops [44] from neighboring crops and wild hosts.

Therefore, exclusion mesh may also be contributing to integrated pest management (IPM) for other cherry pests. In addition, the structures required to grow cherries or other fruits under cladding can be utilized for the mesh system, removing the need for purpose-built frames and additional costs. D. suzukii can move between crops and wild areas throughout the season [6,45] and cherries are one of the first ripening commercial crops in temperate growing regions [46], hence the use of insect mesh can drastically reduce the occurrence of the pest within cropping areas [43].”

The conclusions of this paper not surprisingly include the following:

“Within the manuscript we also highlighted the importance of IPM strategies that can be incorporated into cherry production to not only alleviate the pressure caused by D. suzukii in crops but also to reduce resistance build-up to effective plant protection products.“

I also point out the following four papers.

Del Fava E., Ioriatti C., Melegaro A. Cost–benefit analysis of controlling the spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura)) spread and infestation of soft fruits in Trentino, Northern Italy. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017;73:2318–2327. doi: 10.1002/ps.4618. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Leach H., Moses J., Hanson E., Fanning P., Isaacs R. Rapid harvest schedules and fruit removal as non-chemical approaches for managing spotted wing Drosophila. J. Pest Sci. 2017;91:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s10340-017-0873-9. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Lang G.A., editor. Growing Sweet Cherries Under Plastic Covers and Tunnels: Physiological Aspects and Practical Considerations. International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS); Leuven, Belgium: 2014. [Google Scholar]

16. Lang G.A., editor. Tree Fruit Production in High Tunnels: Current Status and Case Study of Sweet Cherries. International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS); Leuven, Belgium: 2013. [Google Scholar]

There is this, too:

I can’t escape the impression that many of these Dutch cherry growers – the same ones that didn’t stick to the conditions for having the exemption? – don’t want to put in the extra effort that pre-fruit care takes. Apparently, there are about 100 cherry growers in the Netherlands. That makes the bad apples among them identifiable, I’d say.

I picked lots of cherries as a child, on my grandmother’s farm. I’ve also picked lots of strawberries and many other types of berries, such as blackberries in our own pretty large garden. I’ve harvested many beans and some other vegetables, too.