Why these logos? Because images speak louder than words and can convey a lot in a just a fraction of a second.

My focus has been on bioethics for over a decade. This has a lot to do with otherization and diversity.

I’m based in the UK, but I’m a Dutch citizen. It’s fair to say that I’ve been experientially investigating abuse, povertyism and gerontophobia from civil servants as well as homelessness in the Netherlands since roughly the second half of 2023.

Below, you will likely find far more detail than you will want. That makes it a messy page with a lot of waffling, but maybe some of these small details will help inspire a few teenage girls to venture into a STEM career or become a vet. I had to create my own path and came a long way. Most of the time, there wasn’t anyone around to support me or advise me. I wanted to have my own research group but had no idea of how to do that. The only thing that was clear to me from the start is that it requires money.

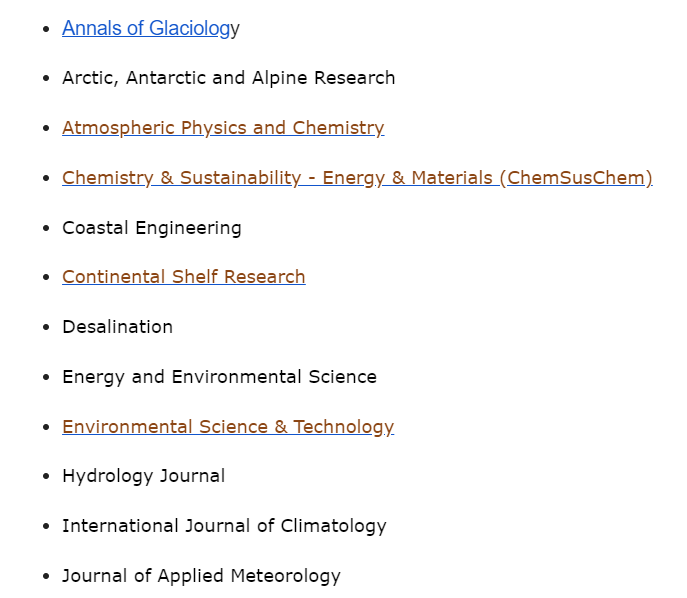

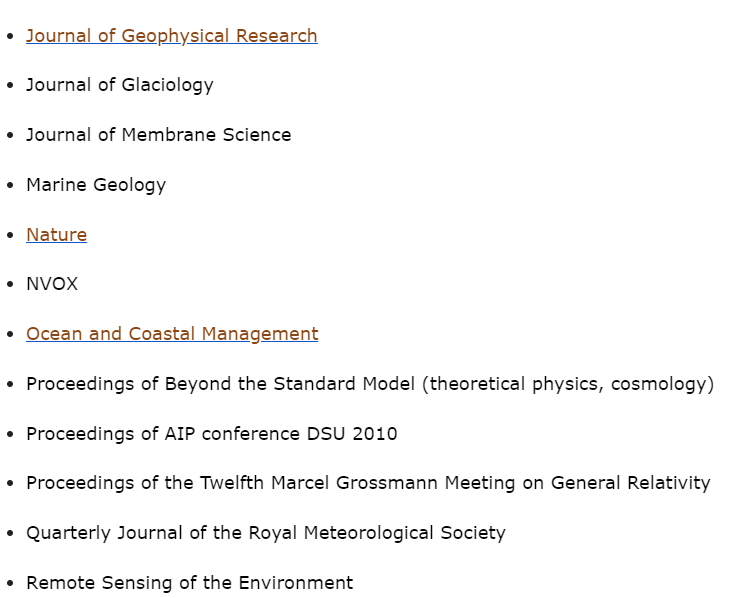

Now I’ll first show you a few logos of clients that I have worked with from within my original professional background, namely earth, marine and environmental sciences. I was a self-employed knowledge worker for over two decades, initially in Amsterdam in the Netherlands. In 2004, I relocated to the UK and took my business with me.

Here is your first surprise.

I probably should have become a vet. ☺️ I did not pursue that because I mistakenly believed that I was squeamish and could not handle the sight of blood. This was related to something that happened in my childhood, when I was 4 or 5, but that I had forgotten about.

I grew up with all kinds of animals in my life, including dogs, horses, cattle and cats. I really enjoyed interacting with them.

While volunteering in wild-bird rehab in Florida, when I was in my mid-thirties, I noticed that I had no trouble at all assisting with medical procedures and witnessing necropsies. In fact, I once got called to assist in a hurry when I was cleaning materials outside and someone else had fainted.

I have looked into whether I could still become a vet, in three different countries, but it wasn’t possible. Instead, I rehabbed a few pigeons later. I learned a heck of a lot from that, as well as from the two non-releasable feral quaker parrots that I adopted from the bird hospital in Florida and emigrated with twice.

Identifying what is ailing a bird if it is not injured is a matter of patiently making observations and combining that with knowledge and research (and also experience, if available). This particular bird also taught me a lot about pigeons. It became bored and decided to set itself challenges to beat the boredom. The next pigeon I rehabbed taught me a ton more. Birds are amazing creatures. They are highly intelligent and capable of compassion, but each has its own character, just like humans. Birds, however, have been on the planet far longer than the human species and probably have a deep understanding of how the environment works in ways that escape humans. If only we could access that knowledge.

Your second surprise is that prior to venturing into earth, marine and environmental science, I explored my options for becoming a pilot. My eyesight isn’t perfect, however, and in those days, that was a major obstacle.

Your third surprise may be that I also looked into computer science when I looked into what I wanted to do. I obtained the book list from the computer science department at VU University Amsterdam (Tanenbaum) and purchased a few books. I was interested in AI; the first AI wave was happening then. However, I was concerned that computer science was too limited and I realized that I wanted something more multidisciplinary. The earth sciences require you to have some grasp of biology, chemistry, physics, math, programming and languages. I had myself tested thoroughly at a career counselling business in the course of a week. I particularly wanted to know about my weak spots.

Here’s your fourth surprise. I was working in tourism & hospitality in Amsterdam at the time. I went to university a little later in life than is usual. I did a semester of German language and literature at Leiden University, but I couldn’t see myself teaching German grammar later. I simply was more into the sciences. My parents had little more than primary school and I was the eldest, so I had a long road of discovery ahead of me.

Earth, marine and environmental science

As I indicated above, my primary background is in the earth & life sciences, with an emphasis on chemistry. Specifically, I’m a geologist (with an emphasis on chemical aspects) and marine biogeochemist (more details below).

Business owner

- Besides the business that I talk about below, I later started up two other businesses that each went nowhere so rapidly that I shut them down within a year.

Legal insights

- In addition, I have good legal insights. ⚖️ I have acted for myself in English courts and negotiated a settlement with lawyers from insurance companies, one of which was a lawyer from a solicitor’s professional negligence insurance firm, the solicitor coughing up 50% of the settlement sum. I’ve also taken a few online courses at Harvard Law School. Maybe I should add that I worked at magic circle firm Clifford Chance as a legal secretary while I was also employed at VU University Amsterdam.

Bioethics

Bioethics combines law, science, technology and the sciences as well as philosophy (which is also part of law) and social sciences.

I have increasingly been occupying myself with bioethics-related topics and activism for the past ten to fifteen years. This came about as the result of having become the target of someting known as sadistic stalking. It made me look into personality disorders and neurodiversity. It combines well with my science background as well as with my grasp of legal matters and I’ve always had a strong drive for justice and fairness.

I don’t have that from a stranger as it turned out. Gérard Herberichs (lawyer and political scientist at Council of Europe) and his sister Céleste Herberichs (psychologist, researcher and journalist) were kindred spirits, each cousins once removed (my mother’s cousins).

Bioethics is a highly multidisciplinary field covering a broad range of societal challenges. It is tied to (in)equality, otherization, marginalization, cruelty, (neuro)diversity etc and even speciesism. There are also clear links to the STEM fields, of course.

My science career in more detail

I started a small business in 1997, in Amsterdam. I wasn’t making a fortune but it enabled me to be living in a way that I really liked (on most days). It brought me a lot of freedom and a wealth in terms of learning opportunities. In 2004, I took that business with me to the UK. The plan was to move back to the US a few years later.

I have worked with and at universities in, mostly, the Netherlands, the UK and the US, in employment as well as in self-employment. I was one of the first in the Netherlands to offer presentation skills training for scientists, together with my business partners Russell Hollamby (Inovaire) and Pinkney C. Froneberger (ICTB). We provided two workshops on site at NATO C3 Agency. “We want our scientists to show more enthusiasm.”

Dutch universities weren’t quite ready for that idea yet. For those clients, I for example helped design and teach a modelling exercise (SOBEK, tidal rivers) and worked on their climate change research papers.

For projects like those and work for publishers and various agencies, I cooperated with Marianne Kerkhof (Netherlands), Julie Siler (US), veterinarian Dr Geerling (Netherlands) (whose first name completely escapes me right now), Victor Cuellar (US, Spain), Anna Dydyk (Canada) and others. Anna and Julie for example proofread manuscripts when I was flooded with work. They saved me precious time and it never hurts to have a second pair of eyes.

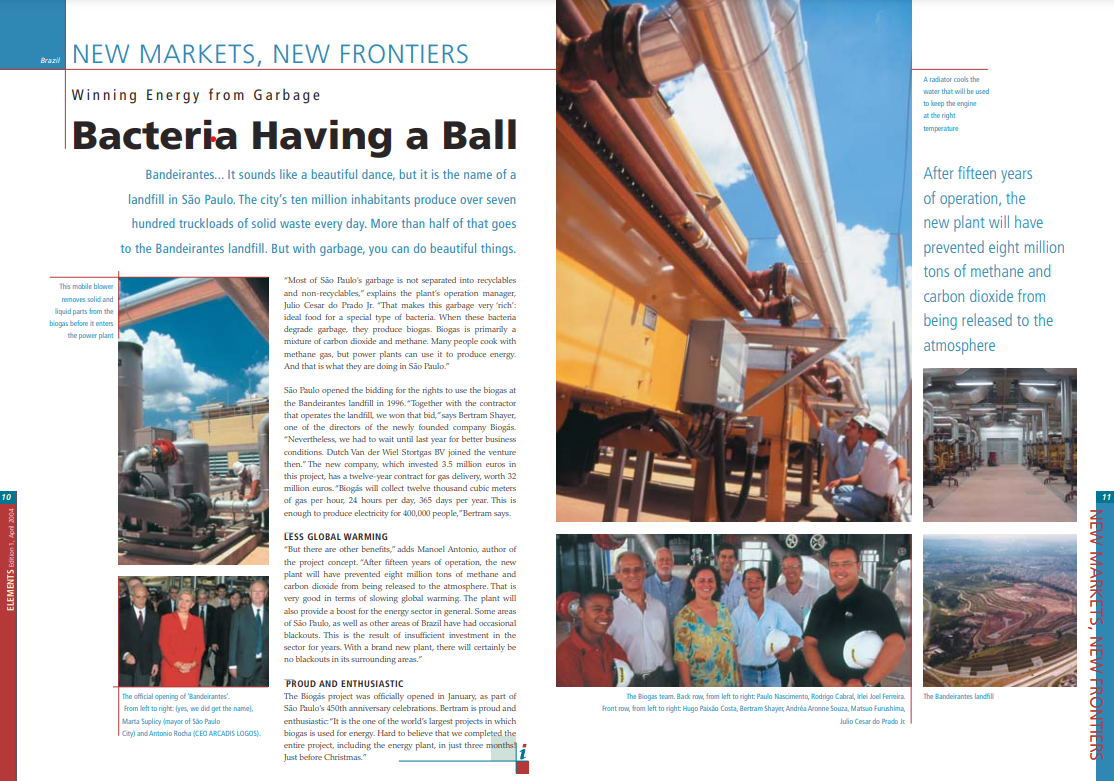

Through my business I also worked with, of course, publishers and various companies such as ARCADIS.

I have served as Associate Editor for the US-based Geochemical Society, as board member of the Environmental Chemistry (and Toxicology) Section of the Royal Netherlands Chemical Society and as board and committee member for a Dutch foundation for women in science and technology (founded in 1988 but no longer in existence). In England, I briefly was a member of the Portsmouth Environmental Forum, launched and supported by Portsmouth City Council (no longer in existence). I’ve also been a member of the ASM, AGU (and convened a session at one of its meetings), AAUW, KNGMG and an affiliate member of IUPAC

I’m a former member of Toastmasters of The Hague, a former member of a Southampton-based business club and a former member of the Amsterdam American Business Club. Business clubs are about business networking, not about booze-filled scenes that many people associate with “club” on the basis of what they’ve seen in films and TV series. Toastmasters predominantly teaches public speaking skills but is great for business networking too.

As a private person (not through my business), I’ve also temped and been employed at a wide range of businesses and organizations, ranging from an E&Y (then MEY) trust company and an international law firm (Clifford Chance) to a large holding (KBB, which owned Bijenkorf, Hema, Praxis and FAO Schwarz) to a government department (agriculture) and IT companies such as Verity and Ideta.

How I got to and departed from VU University Amsterdam

I used to work in tourism and hospitality in Amsterdam. That was after a very brief stint at the University of Leiden, where I enrolled in German language and literature. I was a whizz at languages. I had explored studying geology when I was still in secondary school, as I’d been into collecting rocks and into mineralogy. The university study guides that I ordered stated that you not only had to be really good at the sciences if you wanted to enroll in geology, but that you also had to be in such good shape that it was advisable to get a physical before you applied. It sounded highly discouraging. I graduated summa cum laude from secondary school. Then I went into tourism and hospitality in Amsterdam, but I soon discovered that I didn’t want to be stuck in a low-level job for the rest of my life. Though we often had a lot of fun at work, it wasn’t challenging enough.

After having taken a flying lesson, reading lots of aviation magazines, exploring whether I could become a commercial pilot (which was very difficult back then because I’m slightly near-sighted), and having applied for air hostess positions unsuccessfully three times, I had myself tested extensively for strengths and weaknesses at a career advice agency. I subsequently quit my job and enrolled at university as a full-time earth science student, rekindling that interest from my teenage years. I was in my mid-20s then. For about 18 months, I still occasionally helped out at my previous place of work, a large conference-type hotel which happened to be close to the university.

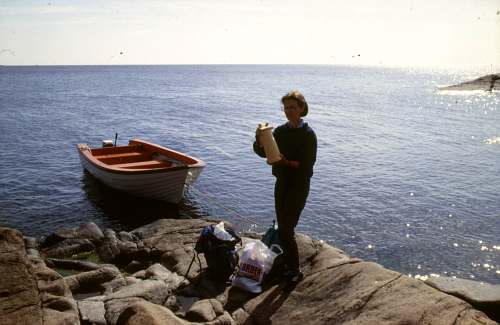

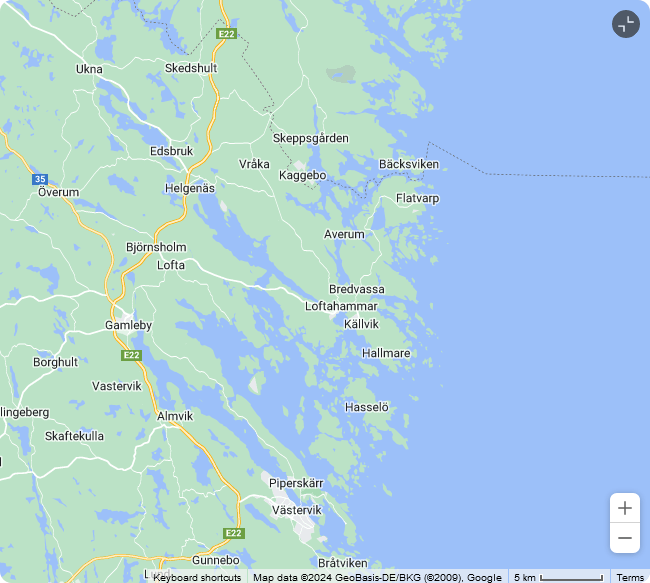

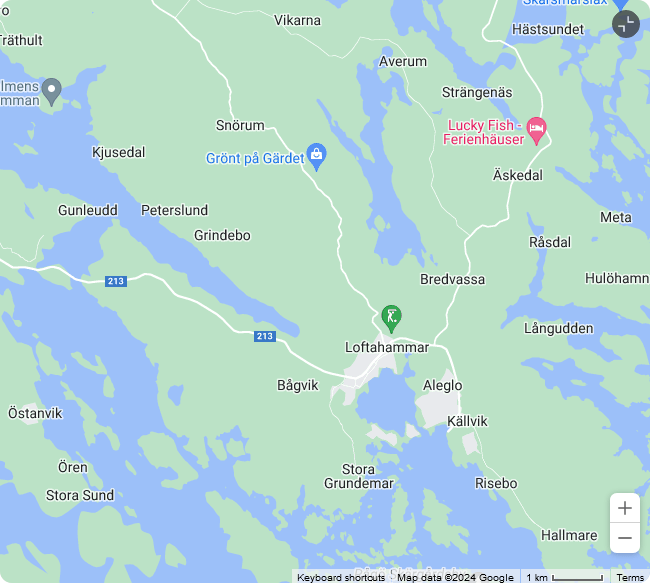

I hold a Master of Science, with distinction (aka “cum laude”), in isotope geology, petrology and geochemistry from the Vrije University of Amsterdam, where I studied the geochemistry and structural geology of the Precambrian of the Loftahammar area in Sweden (near Västervik). Historically, this area was believed to be folded, but my findings of a dominating sense of rotation along with the presence of (ultra)mylonites (toward Helgenäs) indicated that it was more likely to be part of a shear zone. I shipped 500 kilograms of rock samples to Amsterdam, many of which underwent chemical analyses, but their geochemistry yielded no remarkable conclusions.

As part of my degree requirements, I carried out a study into gender bias in sociobiology. I also investigated the then brand-new developments of scanning tunneling microscopy (1986 Nobel Prize) and atomic force microscopy (basically still in development then). I shared my findings with the department in a presentation as well as a report.

I obtained certificates from the Netherlands School for Journalism and the aforementioned extracurricular graduate diploma (with a grade of 9.0 out of 10.0) for research into rare earth elements (REEs) in waters around Antarctica (Weddell Sea and Scotia Sea), carried out in conjunction with the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research. With my co-authors Hein de Baar and Johan Schijf, I presented a poster with the first REE profiles for the Southern Ocean at two or three symposiums. For my participation in a symposium in Bremerhaven, Germany, I received a full conference grant from the European Science Foundation.

Symposiums and conference session organization

During my Master’s, I co-organized two symposiums for women in science and technology in the Netherlands and besides being active in various roles in the related foundation, I was also a member of the Studium Generale committee at the university.

The symposium described in the Dutch TU/E announcement you see here was titled “Op naar de top” and took place in Utrecht. We had contemplated asking Margaret Thatcher for the panel discussion; she had a chemistry background (and so does Angela Merkel, by the way). I don’t remember whether we reached out to her.

Below, on the right, from left to right, physicist Hélène van Pinxteren, physicist Ankie van den Berg, mathematician Ietje Paalman-de Miranda and biologist Anne Mie Emons. On the left, an announcement at TU Eindhoven.

Sylvia Barlag is a physicist and a former Olympian. Nell Ginjaar-Maas was in government, and our replacement for Thatcher, so to speak (but she was ill on the day of the symposium). She too had a chemistry background. Liesbeth Kosters is a geologist who back then had been living in North America until recently. Anne Mie Emons is a biologist. Marjan Heesterbeek also has a chemistry background, as it happens. Aïda Paalman-De Miranda was a mathematician.

Ankie, Ietje, Anne Mie and Hélène (and venue staff)

For the next symposium, titled “Onderweg”, our panel included American geophysicist Lisa Tauxe, R&D physicist Ankie van den Berg of Hoogovens, Hanneke de Bruin, Noortje de Graaf, Willemien Alberts and a woman whose first name was Mechteld, I think, with my apologies to “Mechteld” who worked at HP.

(I also served as interpreter for Lisa Tauxe during this panel discussion.)

I also convened a session of the 1998 AGU Spring Meeting in Boston (molds and fungi in the marine environment), for which I received a grant from Stichting Fonds Doctor Catharine van Tussenbroek.

During a later symposium of this organization for women in science and technology in the Netherlands, I was one of the panel members.

My life in the US and UK

After I graduated from university, I moved to the States because I was considered too old to start a PhD in my native country. The Amsterdam job agency kept referring me to secretary and typist vacancies, nothing else, and not even at universities or technology companies. I turned out to fit much better into American culture. I felt at home there. Life’s a lot more fun in the States.

At the University of South Florida I investigated the marine cerium anomaly and stumbled upon the potential role of enzymes of fungi (notably manganese peroxidase). Unfortunately, we lost our research funding and my PhD got cut short.

I had burned my bridges to be able to move to the States. In the Netherlands, I was then definitely considered too old then; someone even literally wrote to me that it was time to step aside for younger people. I was only in my 30s. I eventually started my own small business, which is probably the best decision I ever made.

I also obtained a certificate for auditorium teaching from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, but I prefer one-on-one teaching. It’s much more demanding but also much more invigorating as well as more effective. I’ve been told that I am a very patient teacher, by a former teacher. Students have also told me that they appreciate what I contribute. Part of the reason why for a long time I wanted to be a professor was that I discovered that I really enjoyed coaching and supporting students.

However, it had been my goal to have my own research group and I’d also now learned that the Netherlands was definitely not the best country for me, for several reasons, including its high level of air pollution and its climate but also its culture. So I eventually moved to England which was supposed to have been for only a few years. At the University of Southampton (NOC), initially at the University of Plymouth, I looked into the exchange of atmospheric iron at the sea-air interface against the background of the impact of rising atmospheric CO2 on ocean acidity as well as the resulting switching between cobalt and iron pathways in marine cyanobacteria.

At the University of Southampton, which is a founding member of the Russell Group (the UK’s version of the Ivy League), I discovered that I really enjoyed running my small business, from which I had already learned a heck of a lot. I declined a paid PhD position, gave up on my goal of becoming a full professor and left the labs behind me. I’ve worked with and at other universities and scientists too, mostly in self-employment. I have also worked with and at various companies and other organizations.

Wildlife rehab experience

In Florida, I volunteered with the well-respected seabird rehabilitator, educator and oil spill contingency planner Lee Fox, who often worked with organizations like NOAA and who was for example involved in the cleanup after the Prestige oil spill in Europe. In some countries, volunteering is mainly for unemployed, disabled and retired persons; that’s never been the case in the US, where people are often much more proactive and more community-minded. One of the marine science professors there was heavily involved in birds-of-prey rehabilitation in his spare time, for example. So I also know a thing or two about rehabbing wild birds.

In Florida, I adopted to non-releasable quaker parrots (Myiopsitta monachus) and I’ve later worked with and equally smart and spunky species (Columba livia).

In the first twenty years of my life, there were cats and cattle, horses and dogs, stick insects and other critters in my life. I used to roam the moors or heathlands and woods behind our home; it was in an urban setting but on the edge of a large nature area. (I started running when I was still in primary school; I was very fast.) I’ve later rescued two cats off the streets, after already having adopted one from a shelter.

Geological fieldwork during my Master’s

I’ve also done fieldwork in the Buntsandstein near Gea de Albarracín, a year later, in central Spain (Aragón). There, I became fascinated with the iron in the field (trivalent in sandstone but divalent in clays), an indication of things to come.

A year earlier, I was in Yecla, also in southeastern Spain (Murcia, about 80 km from Alicante). It had nothing but limestones. I couldn’t make much sense of them and had to give up. Yecla is a lovely place, by the way. I think I was also dealing with some childhood issues that I didn’t know I had, but I don’t know whether that played a role in my failure to complete the fieldwork. Probably not. The Yecla area was no longer used for students after that year. There were many students in my year (over 70) and for that reason, we’d already been split into two groups from the beginning and areas had to be found for all of us to do fieldwork in.

We all learned that when you get stuck with your map – we carried out these fieldworks in Spain to make geological maps, you see, to learn how you do that – Anís can help a lot. It’s the Spanish version of Pernod.

I used to spend a lot of money on my maps. I made mine on some kind of special film and I had several Rotring technical drawing pens. I went to a commercial printer that could handle the large format, the kind of place where they also handle architects’ blueprints. I vaguely recall that most students did not use the film (I don’t know what they used instead) and had the maps printed at the university department. As the way I did this cost so much money, I may not always have used the film and I seem to recall that I didn’t do it for my Sweden fieldwork, only for my Spain fieldwork. I also bought a car for my Sweden fieldwork.

This car turned out to have a peculiar problem… Its engine was missing a few bolts and so the engine was increasingly running on air. I replaced the battery. That didn’t help. The issue got worse and worse and I took the car to a garage in Loftahammar. After the carburetor had been opened and was found to be pretty clean, the mechanic dropped a wrench and happened to look up when he picked it up. That’s when he spotted the missing bolts issue.

While on fieldwork, I also accidentally parked the car in a totally overgrown ditch, not once but twice, but that was not related. Helpful Swedes towed me out.

I stayed in a stuga that had no electricity, no running water and only bottled gas. The rent was higher than the rent for my apartment in Amsterdam.

Why am I adding so many of these details? Lay people often think that scientists spend their entire lives peering down microscopes or swirling stuff in test tubes and poring over books in their labs. They also teach, do PR, give presentations for their colleagues, plan and have meetings, write, hire and fire people, network, travel and apply for research funding.

If you’re in the earth or marine sciences, it certainly involves a lot more than microscopes and test tubes. This also goes for some biology and most environmental science and definitely for ecology.

I shipped 500 kilograms of rock samples from Sweden, as mentioned. I also had to process them, that is, have them cut, often very precisely along certain directions. You have a compass with you when you do fieldwork, not just to orient yourself, but also to measure orientations in rocks. You also often write down orientations on your samples before you remove them and you always number them. On your map, you indicate where you took your samples. I crushed and milled many samples and even melted some of them, for microscope slides called thin sections and for all kinds of chemical analyses, such as XRF.

By the way, you also have to find a place to stay when you’re doing fieldwork. It’s not arranged for you, except on the field trips that precede your solo fieldworks. For me, those field trips – up to two weeks – went to places in Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Scotland.

Once you get out of this hands-on stage, as an academic scientist, you increasingly become more like a business manager, however. Most lay people probably have no idea of that.

Besides the previous background in tourism and hospitality, I also have an understanding of some areas of English and American law. To be more precise, I’ve worked at Magic Circle firm Clifford Chance, albeit as a legal secretary to top up my income (so mostly evenings, nights and weekends), and I’ve been successful as a LIP (pro se) in England. I’ve also successfully dealt with some legal issues in the States. The photo to the right shows me at my desk at Clifford Chance. Someone snapped a photo.

Feedback

“I wish I could hire you – instead of those flashy guys in their expensive suits. They send me hastily written reports for which they charge me hundreds of euros per hour. You’d charge a lot less and I’d get such a much more thorough job from you. But you’re not based in the Netherlands, so I can’t.”

~ Hélène van Pinxteren (†), in her capacity of senior policy advisor at the Netherlands’ National Science Foundation NWO, about strategy research

She and I had known each other since 1988. We got to know each other well when we co-organized a symposium or two, which included doing things like calling journalists and politicians together. I had previously visited Hélène at AMOLF as I was interested in Hélène’s PhD research and in the scanning tunneling microscope that the AMOLF was building at the time. We met up again after I returned from the States and also shortly before Hélène passed away. She’ll always remain one of my favorite people.

“I know very few earth scientists with her broad range of expertise and experience. In addition, Ms Souren is blessed with golden penmanship and an iron will.” ~ FB, in his capacity of geologist at VU University Amsterdam

“highly creative” and “I’ve never done this before, I’ve never before said ‘go ahead, take the lead on this to a PhD student.'” ~Bob Byrne, USF

I started developing a research proposal for ILZRO because we’d unexpectedly lost our funding. Writing with Byrne was a joy; he is a very skilled wordsmith and he wants papers to be perfect. I really liked that work ethic. I basically learned how to write papers and proposals from him. Lay people tend to think that writing and editing papers and proposals is something that secretarial staff does, that real scientists spend their days peering down microscopes and swirling test tubes, but Byrne is a distinguished research professor. (That’s an academic title in the US, given to top tenured full professors.) He’s also an entrepreneur; when he couldn’t get academic funding for something that he wanted to develop, he and some colleagues started a company. It became rather successful and even went international. It still exists, operates under a different umbrella name now, serving a broader market.

Angelique Souren betoonde zich een gezellige en zeer ijverige bijvakstudente. Door haar inzet zijn monsters van de Southern Ocean geanalyseerd die anders zeker waren blijven liggen. Haar volkorenkoekjes hebben mij gedurende lange meetnachten en -weekenden op de been gehouden. Ik hoop dat zij het onderzoek als o.i.o. zal kunnen voortzetten. ~J(oh)an Schijf, RUU

(Nope, I did receive the oio employee paperwork but when I returned it, they realized that I was much older than they thought. I was considered too old. This certainly played a role for women, who were considered risky as they were expected to want to have children and then cease their careers. For men, being married was a plus as it signified support. For women, it was considered a drawback. I wasn’t married, but my age still made me too high-risk in view of my employer’s unemployment benefit obligations.)

10 out of 10 and 9 out of 10 etc, voluminous report etc ~Hein de Baar, NIOZ

Thinking of Hein still makes me smile. Hein was very driven; so was I. I like people who are highly driven even though it also means that you sometimes butt heads. But each gets where the other person is coming from. Jan Schijf was the one who taught me to avoid contamination at picomol/kg concentrations and how to process (chromatography), spike (with isotopes) and measure (ID-TIMS) my ocean water samples.

“Thank you for your attentiveness. We’ve already followed it up enthusiastically.” ~ Carla van Dokkum, in her capacity of communications manager at Arcadis

I worked with Carla on the Elements magazine team; she taught me how to write snappy, non-scientific articles (though I’d taken an evening course in journalism before). I had spotted a sponsoring opportunity for Arcadis that they couldn’t possibly ignore. So I let them know.

That same attentiveness helped me prevent that USF’s Department of Marine Science missed out on several hundred thousand dollars in matching DEP or FMRI – now FWRI – funds for an ICP-MS.

In my self-employment, I’ve later worked on research proposals that together have earned well over 10 million in grants. (I didn’t keep a tally and not everyone reported back to me later.) Grant proposals are often submitted in a great rush to meet the submission deadline. They’ve occasionally required me to pull an all-nighter.

“I felt really well supported by you.” ~ Mireille Oud, a medical physicist who’s hired me several times to work on grant proposals and other materials

“You are highly conscientious.” ~ Mirthe van Kesteren, in her capacity of international lawyer at Clifford Chance, where I topped up my income for a while

“Holy cow, you did such a great job!” ~ Robyn Hannigan in her capacity of professor at Arkansas State University about my work on a paper

I’d encountered Robyn in Woods Hole in 1998. She and a colleague noticed me at a lecture, talking with the dean and with a researcher who had called that dean when he learned that, while he had thought that I was a fully fledged professor because I’d written a comment on one of his scientific publications, I didn’t even have a PhD yet. The women then approached me at the AGU conference in Boston, which I was there for. Robyn’s hired me a few times since, to work on papers and grant proposals.

I’ve had similar feedback from others, such as Albert Janssen (though that is someone I’ve never met and probably never even spoken with). People also often praise my versatility, my willingness to take responsibility and my take-charge attitude. They’ve used terms like sparkling, workaholic, creative and driven to describe me. I’ve also received praise for my teaching skills. I’m more of a hands-on, one-on-one teacher than an auditorium lecturer, because you get to have a better connection during hands-on teaching (think labs). It can really drain your energy, but it’s invigorating at the same time.

A little personal background to wrap it up

I’ve always liked to be at the cutting edge as I love learning and am very much curiosity-driven. I also like momentum and having a lot of freedom so 9-to-5 desk-jockeying paper-pushing jobs have never been quite my thing. When I grew up, I loved roaming the woods and moors. I enjoyed dealing with farm animals and pets. I loved running and sprinting as well as reading and doing my own writing, and also singing and listening to and playing music.

I’ve always been a feminist. I don’t consider women flawed specimens of the species. When I was in primary school, I noticed that the women with the more interesting lives and with more fun and education in their lives were the unmarried ones, particularly also nuns.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I volunteered in the vaccination effort by taking on a steward role at a local vaccination center, in the rush for booster jabs just before Christmas.

In the early 1980s, I started teaching myself Basic. I’ve worked with DOS and Windows computers since about 1986, with Macs since around 1990 and with Linux systems since roughly 2012. I learned some Turbo Pascal and some Unix in the middle 1980s, have built computers and I’ve also created (large) websites in notepad.

I became a Wikipedia editor in 2011; I ceased contributing to Wikipedia on 21 July 2025 in protest against the misogyny and unethical practices there. Only a small percentage of Wikipedia’s editors are women (15% in 2024) and that continues to impact Wikipedia’s content. Women for example were often described in terms like “former partner of” instead of their own merits and certain professional areas were underrepresented. I should also definitely add that most lay people don’t know how Wikipedia pages come about and tend to make a whole slew of incorrect assumptions about the process.

My parents had literally little more than primary school so I’ve had to invent the wheel many times along the way – and I’ve come a long way.

- I’m using the strange circumstances in which I ended up in 2025 as a platform – a vehicle – for my activism. It provides the so-called hook that previously was lacking.

- Other than that, my focus is on online trading these days. I like it and it’s the only way in which I will be able to generate an independent income again in the future. (I’m not eligible for any kind of financial support from a government, but my pensions will start kicking in in a few years.) My current trading capital is a whopping 200 euros and I don’t always have access to the markets so the going is a little slow.

- I haven’t been able to support myself since I moved from Southampton to Portsmouth at the start of 2009 and have gotten pretty good at doing as much as possible most with very little.

- Therefore, I currently depend on donations via PayPal, GoFundMe etc.

- I also get a tiny bit of income – peanuts – from books I’ve written and courses I’ve created as well as royalties for science books that I translated and adapted as part of my past self-employment.