Usually unwittingly, people with Asperger’s can be quite mean (and sometimes bullies), in my experience. I wouldn’t call it malice. It’s fuelled by powerlessness.

One of the problems with Asperger’s and other forms of autism is that autistic people don’t seem to realise that allistic people are just as bewildered and mystified about how they think and behave as they are about how allistic people think and behave.

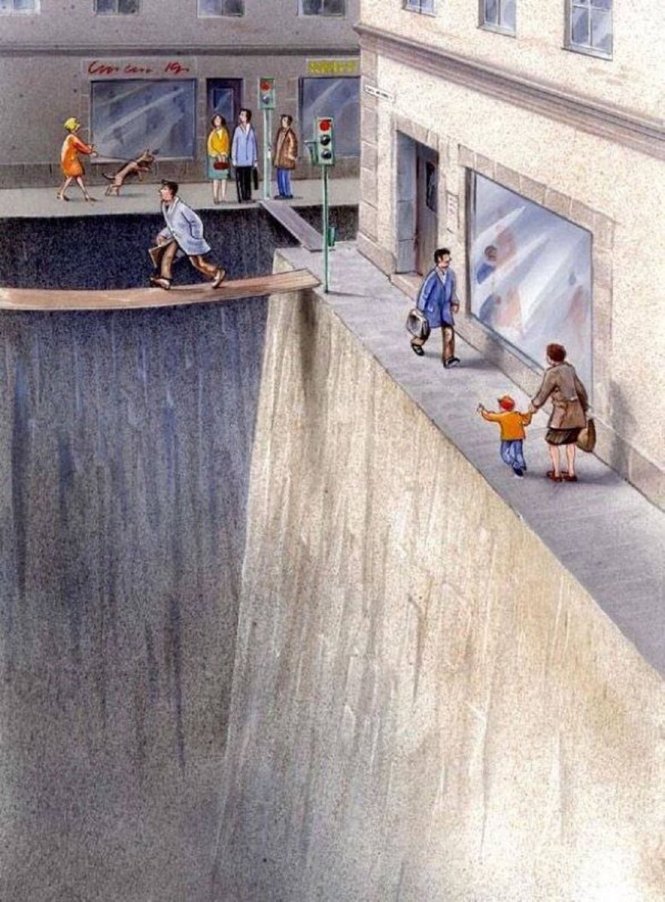

How do you bridge that gap? I have no idea, but this image comes to mind.

I am allistic, intelligent, close to being an empath but not a full empath and pretty middle of the road otherwise. I occasionally have CPTSD-like flareups, but I don’t have CPTSD. The past two decades of my life simply have been pretty bonkers. I’m exhausted. I’m also angry and frustrated (fed up). Been living like a cross between a zombie and a circus monkey for too long.

I have two to four decades of experience with three or four people with Asperger’s, with one person with covert narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) over the course of three decades and about two decades of experience with someone who I later assessed as having a borderline personality disorder without any addictions. For one year, I had a colleague who talked openly about her dissociative identity disorder (DID) and where it stemmed from (satanic abuse as a young child, among other things resulting in a hysterectomy at a relatively young age) and in the course of 15 years or so, I have often cooperated with a woman who has well-managed bipolar disorder. She’s had to fight for that.

I get the impression that autistic people are almost completely driven by their senses. They focus on how they feel and what they like and dislike in this regard. What this can lead to? Poor impulse control (giving in, followed by demand avoidance). Jumping to conclusions, and it’s probably often the wrong one. 🙃😁

They have great empathy and can be (or act) warm, attentive and generous, but they tend to appear to have difficulty imagining what it is like to stand in someone else’s shoes. “You need a wok.” (Because he often uses a wok.) “Did you take the light fixtures when you moved out?” “Light fixtures? What light fixtures?”(It’s also probably the least important thing to worry about, considering the circumstances in this case. Overwhelmed?) (His, from his previous apartment, seem to be permanently sitting on the floor of his current apartment, however.)

I suspect that they also expect to be let down by allistic people as a rule.

This being driven by feelings can for example result in meanness when the person with Asperger’s harbors what I shall call romantic feelings here (even though these feelings are usually merely physical and from his or her point of view only) and then discovers that the woman in question is not interested. I think that it is usually very hard for autistic people to assess whether someone is genuinely interested in them and has their best interests at heart. I also suspect that their “love” often looks like infatuation or besottedness (puppy love?), from an allistic point of view. It’s complicated.

It’s related to how the brain is wired. It is not wired the same way in everyone (and those differences tend to show up in scans). This makes clear to mainstream people that those others are not just attention seekers who can change their behaviour at will.

THIS IS DIVERSITY.

(S, if that was you, I don’t think that this is what you look like or come across like. Dark and brooding or at least pensive is my impression. Quiet, not loud and exuberant. Someone who silently sits on the seashore or on a hilltop. I think I have have seen this kind outward “explosion” of boundless energy only once, in August 2008. I mostly saw a hurt little boy, someone screaming for attention, and possibly lashing out at the world a lot.)

I think that diversity is a huge multidimensional space in which we all take up a unique spot. I also think that there is some kind of continuum between autism and narcissism. Both have issues with loyalty and abandonment (but this is also the case for people with borderline personality disorder).

I am starting to think that the more physical differences there are relative to allistic people when someone is autistic, the lower the tendency for what you might call malice or meanness.

The “meanness” (powerlessness) may get expressed more often physically, through for example kicking or biting, however. These are not regular tantrums and this doesn’t concern bad parenting. These children and adults want to be reassured and soothed, made to feel safe and more in control. What this means in practice differs. There is no “one size fits all” approach.

What most of us perceive as psychopathy actually reflects a complete lack of feelings. That’s a different beast. Sociopaths – no longer an official term – are bewildered by other humans.

For the record, this area is NOT my profession. I am saying these things on the basis of my personal experiences and observations as well as reading and listening.

People with Asperger’s often use a different kind of logic and also often have trouble making sense out of allistic people. This can cause a lot of anger and frustration, even resentment.

Some use for example Le Petit Prince as a guideline for how to interact with others.

They CAN push people’s buttons just to see what happens next, in order to “study” them.

This CAN be in combination with resentment, as mentioned.

This CAN go pretty far.

This CAN take place in the form of a Jekyll & Hyde setup.

See also perhaps for example the following as well as the references at the bottom of the article by Digby Tantam:

– High functioning autistic spectrum disorders, offending and other law-breaking: Findings from a community sample (article by Woodbury-Smith et al. in Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology)

– Asperger’s disorder and criminal behavior: Forensic-psychiatric considerations (article by Haskins & Silva in J Am Acad Psychiatry Law)

– Autism spectrum disorder and psychopathy: shared cognitive underpinnings or double hit? (article by Rogers et al. in Psychological Medicine)

– Married with Undiagnosed ASD: Why Women Who Leave Lose Twice April 20, 2016 (by Sarah Swenson, MA, LMHC, GoodTherapy.org Topic Expert)

– How to spot Asperger’s (https://theneurotypical.com/how-to-spot-aspergers.html):

– Open letter to experts in ASD/ High Functioning Autism (this link is to a PDF on this site; I have pasted its contents at the bottom of this page as the original is on a non-secure WordPress website so your browser will likely protest if you try to access it. http://www.aspergerpartner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Open-letter-to-experts-in-High-Functioning-Autism.pdf

Below is an article by psychiatrist and psychotherapist Digby Tantam (link to Wikipedia page) that I copied and pasted because it may look a little unreliable on the site from which I copied it (link) and I don’t want you to be put off by that.

Malice and Asperger’s

Doris Lessing, in her novel, The Fifth Child (Lessing, 1989), describes the impact on a family, previously loving and stable, of having a fifth child. This child in his intransigence and his propensity for outrageous and hurtful behaviour, challenged all their liberal pre-conceptions and brought the family to the brink of dissolution. This kind of maliciousness is not something that is normally associated with Asperger Syndrome: too many sufferers seem too innocent, too law abiding, and too unaware of their own self interest to be described as malicious. Yet this is the best translation of the word that Asperger used for several of the children that he described in his classic paper of 1944 (Asperger, 1944), see (Frith, 1991) for translation. In this paper I shall consider whether children and adults with pervasive developmental disorder can sometimes be rightly described as being malicious; how can this be recognised; and some ideas about management.

A young man with Asperger syndrome rang his favourite Aunt to say that her husband had been killed in a road traffic accident on his way home from work. The report was a complete fabrication as became apparent an hour later when his Uncle arrived home. The Aunt was disgusted at her nephew’s action because she did not feel it was explicable. It challenged her sense of what could be expected in the world. Moreover, she had always thought that she was close to the young man and had, indeed, recently helped him out. The action was therefore inexplicable in a narrower sense, in being undeserved. It challenged another belief that she had always taken for granted that people got their just desserts. It seemed to other family members that the young man’s only motive was to cause mischief and mental suffering, and they wanted to distance themselves from him to protect themselves.

Acts of malice like this include creating unnecessary uproar which stops a social activity from taking place, calling a person names or revealing embarrassing information about them, being spiteful to them in other ways for example damaging their property, or hurting others. These hurts can range from surreptitious pinching through to serious violence. Fortunately, serious violence is rare and may not be more commonly exhibited by people with AS than by members of the general population (Ghaziuddin, Tsai and Ghaziuddin, 1991).

However, when serious violence, arson, unlawful killing or grievous bodily harm may seem undeserved, it is often directed at someone who is vulnerable, and it seems inexplicable because there is little or no apparent benefit to the person with AS who commits the harm. These three characteristics, undeserved, lack of compunction, and gratuitous, are linked to an observer’s perception of an act being malicious. They are each factors which make it hard to identify with the perpetrator. Rather than thinking that ‘there but for the grace of God’, an observer is likely to feel horrified and to want to cut off contact with the perpetrator.

Alice’s parents had split up when she was in her early teens, and her father had remarried a younger woman. Her father and his new wife had a daughter, and Alice was very interested in her. The parents were pleased and several times left the baby with Alice. Alice on two of these occasions mixed ground glass into the baby’s food before feeding the baby with it. Alice knew that this could cause the baby serious harm, even kill the baby. Alice explained her actions by saying that she wanted to see what would happen. She also said that she did not want the baby to die, but did feel excitement after she had fed the baby the poison.

Several features of Alice’s actions often recur in malicious actions by other people with AS. Younger children may be targets, quite often siblings. There is often an experimental explanation given and, afterwards, there is a lack of remorse or fear. The real explanation is elusive. Wing (personal communication) has suggested that the person with AS may harm others in the furtherance of a special interest.

Roger was fascinated by archaeology. Once he had turned 18, his parents thought that they could safely leave him at home whilst they went on a well-deserved holiday. When they came back, they found that Roger had dug up the back garden and re-shaped it into the appearance of a typical archaeological dig. Roger’s explanation, that he thought his parents would get as much pleasure out of his landscape redesign as he did, rings true. Of course, he got that wrong, but his lack of understanding of his parents’ perspective may explain that. There is no sense that Roger was seeking to harm his parents, and his actions do not have the malicious quality that Alice’s do. His pursuit of his special interest was at the expense of his parents but he was not primarily interested in harming them. Alice had no prior interest in poisoning, but her intention was to cause harm or at least to test out her power to cause it.

Richard, for no apparent reason, seemed to target one particular teacher at school. He made slighting remarks about her at first, and then became increasingly crude in his language until she became so distressed that she said to the head-teacher that either he went, or she did. He was barred from her class and when this behaviour was repeated with another teacher, also female, he was suspended from school. Richard was at first considered to be seeking the attention of the teacher, but his behaviour got worse when she tried to ignore his provocative remarks and to attend to him when he was being more appropriate in his behaviour.

Newson has suggested that behaviour like Richard’s is motivated by ‘pathological demand avoidance’. That it disrupts a social situation in which expectations are made of a person, for example the classroom, before the person’s inability to meet those expectations is manifest. Like the attention-seeking explanation, pathological demand avoidance runs up against the problem that the behaviour leads to other kinds of social demand. Richard was, for example, quizzed by many people about why he had behaved as he did and was as much at a loss to answer as he would have been in the classroom.

Elizabeth Newson’s description of pathological demand avoidance syndrome has drawn attention to the existence of people with a pervasive developmental disorder who meet criteria for Asperger syndrome, but who are not currently recognized by professionals. They tend to be amongst the children diagnosed with conduct disorders or adults with antisocial or borderline personality disorders. They present problems because of their apparently malicious behaviour, but they do not strike others as having deficits in non-verbal communication or unusual patterns of interest. The reaction of other people may be very much like the reaction described in Doris Lessing’s book.

Hugo is fifteen. He has been barred from school, and is enrolled in college although he rarely goes. His parents are separated and he has a distant relationship with his father, who has been in only intermittent and unsupportive contact with the family in the ten years since he left. His mother works, and is unsure what Hugo does during the day. Sometimes she comes home to find things broken. Hugo will not tell her what has happened. Hugo has acquaintances, but no real friends. She thinks that he is used by some of his older and more street-wise acquaintances to run errands, and that he may be involved in crime. Hugo is often threatening to his mother, and she is quite frightened of him. He is particularly disturbed if there is any alteration in the arrangements at home, and insists that his mother tells him of when she will leave the house, when she will return, and when the evening meal will be ready.

His older brother avoids Hugo because Hugo has deliberately broken belongings of the brother in the past. He urges his mother to put Hugo out, but she is reluctant to do so because she is sure that Hugo will be exploited by others who are more on qui vive than Hugo himself is. She is aware that Hugo’s self-care needs constant monitoring. He has trouble with change and avoids shopping; he cannot cook without getting mixed up; he cannot keep track of money; and he needs to be prompted about shaving and bathing.

This is a composite account, and the difficulties of a particular person with this type of Asperger presentation will vary. However, there are some important common features.

Firstly, the person with this form of Asperger syndrome (which I shall call TFAS for short) lacks the obvious eccentricity and clumsiness of many of the people who would be instantly recognizable as having Asperger syndrome.

Secondly, the person with TFAS often seems immature and, at first sight, incapable of the actions attributed to them. The appearance of immaturity is partly due to a lack of lines or shadows on the face, as if the person has not lived asfully as most people. This may be true, in the sense that living life involves reacting strongly to it. The appearance of immaturity is also due to the person with TFAS’s lack of social awareness. He or she is often curious and asks personal questions of another person at first meeting, or wants to handle something that the other person has with them. This often seems innocent, almost disarming, but there is something of an edge to it. One is not quite sure whether the person with TFAS is really innocent or is testing the limits of one’s tolerance.

Thirdly, the level of the person with TFAS’ disability is concealed. The account that the person gives of their life avoids or explains away problems of all sorts, including problems in everyday living such as the self-care problems that Hugo had.

The concealment often extends to the characteristic symptoms of Asperger syndrome. A person with TFAS rarely has a special interest but, if anything, they have a lack of interests in the world. Although they may express an interest in football, their interest is not the passionate one of the fan or of the amateur player. It is more as if the person with TFAS knows that some interest is expected of them. In fact a person with this form of Asperger syndrome may spend long periods in inactivity.

Repetitive activity is concealed, too. Parents may report that their son or daughter with TFAS has stereotyped activities which become very intrusive at home, but are usually concealed when the person is with a stranger. Repetitive questioning may be one, but others may be rocking, smoothing the hair, repeating words, or vocalizations. Sometimes these stereotypes are quite similar to those of people who have Tourette syndrome but they are not confined to sniffing or swearing.

As in some people with Tourette syndrome and indeed some young people with obsessional disorder, people with TFAS are more likely than other people with AS to fly into a rage. This explosive anger is frightening can lead to hitting or breaking things. However, it may also have a detached quality as if the person does not feel their anger, only shows it.

It is my impression that the proportion of girls with TFAS is higher than the proportion of girls with other expressions of Asperger syndrome. Girls have a greater range of provocative behaviour at their disposal than boys, and girls with TFAS may create particular outrage because of this.

Tricia who was 12 horrified the school librarian by asking for as many books as possible on the Yorkshire Ripper or, failing that, on other serial killers.

Amanda lived in a small town close to a large Army base. Whenever she saw a soldier she would walk up to him and make a Nazi salute, shouting “Sieg Heil!”. Some months after this, Amanda caused further worry to her parents by disappearing for long periods. She was eventually spotted by a family friend on a motor-bike many miles away from home. It came out that Amanda would go to a particular café frequented by young motor-bikers and would approach one of them, usually a stranger, asking to be taken for a ride.

Felicity used to go to one of the shopping malls near her home, stand in the centre of one of the long, glass-lined isles, and scream as loudly and for as long as she could.

Each of these girls, and indeed each of the people with TFAS that I have mentioned, prompted other people to say, “Why are they doing this?” I do not think that the answer to this question is that these young people are evil or even, as Doris Lessing suggests in the Fifth Child, that they of a different race to humanity. I do think that they are baffled by the world around them, but they are also desperate to conceal that inadequacy.

I think that Elizabeth Newson is right in supposing that there is an element of avoidance in the uproar that people with TFAS cause. However, avoidance is not always the motive as some socially distressing actions by people with TFAS are initiated by them out of an apparently clear blue sky.

The common theme is, I think, a sense of powerlessness which a person with TFAS tries to circumvent by using their power to shock or to disrupt. But this raises a further question. Why should a person with TFAS be powerless? The reason is, I think, because they are very poor at non-verbal communication.

However, their difficulties are not the problems of non-verbal expression that other people with Asperger syndrome have, but problems of non-verbal interpretation. They have difficulty reading other people’s faces, and probably their gestures and tones of voice, too. Being outrageous helps to overcome this problem because other people, when they are very emotionally aroused, emit more and more obvious cues about what they are feeling. And the fact that you have predictably elicited strong feeling in someone else may be more rewarding than the fact that the feeling is hostile or distressing. People with TFAS may seem uncannily good at winding others up, but they have had plenty of opportunity to learn how to do this. What they cannot so easily do is to participate emotionally themselves in the social encounter. They learn about social situations, rather than learning in them. This problem may be associated with other difficulties, like an impaired ability to tell yourself the story of how another person will look at a behaviour, and like the tendency to lump everyone together in the same group of people who are against you. More research needs to be done to find out what the difficulties are precisely.

However, I do know that I now regularly ask people who I suspect of having TFAS to match faces (taken from a widely used set of test faces) by emotional expression and they make many more errors than would be expected given their intelligence. Sometimes parents will confirm that they have noticed the difficulties in this area that their son or daughter has. More often, it has not been noticed before. This is not surprising. It is very hard to spot that someone, say, thinks that you are angry whenever you look disgusted or that you are surprised whenever you look frightened. However, a consequence of the fact that other people do not notice the problem is that the person with TFAS is more likely to conceal their difficulties too. That, or so it seems to me, is the beginning of their real problems. For, in not being able to call on other people’s assistance or support, the person with TFAS finds themselves failing to find friends or to gain influence in social settings. The fact that people with TFAS then resort to coercive means would surprise us less than it does if we were aware of their handicap. I hope that this article may be a small contribution to this greater awareness.

Acknowledgements:

I am grateful to my partner Emmy van Deurzen for her constant support and encouragement to me to understand the personal context in which all of us act.

References:

1. Asperger, H. (1944) Die “Autistichen Psychopathen” in Kindersalter. Archiv fur Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankenheiten 117, 76-136.

2. Frith, U. (Ed.). (1991) Autism and Asperger’s syndrome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

3. Ghaziuddin, M., Tsai, L. Ghaziuddin, N. (1991) Brief report: violence in Asperger syndrome, a critique. In Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 21, 349-3544.

4. Lessing, D. (1989) The Fifth Child. London: Paladin.

(The following was copied and pasted by me, Angelina Souren, not edited other than having removed page numbers. The original is on a non-secure WordPress website so your browser will protest if you try to access it: http://www.aspergerpartner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Open-letter-to-experts-in-High-Functioning-Autism.pdf)

Open letter to experts in ASD/ High Functioning Autism

May 24, 2014.

Try to imagine the following scenario: You live with a blind spouse who is not aware that he is

blind and that other people actually can see. He does not know what “see” means. He has always

been helped by others.

One day, after several years struggle, you succeed in convincing him it is a good idea to consult a

doctor and get a formal diagnosis of blindness. Together you walk into the doctor’s office, and the

doctor asks your husband:

“Tell me, why do you want to have a diagnosis?”

“I don’t know,” your husband answers. “It’s my wife…”

Doctor: “Do you have any problems being blind?”

Husband: “No, I have no problems.”

Doctor: “Well then I see no reason to spend more time here. Have a nice day!”

You tell me this scenario is unthinkable. Of course it is unthinkable if it only concerns a normal

lack of sight. No blind person would ever behave so selfishly and disrespectfully towards their wife

and family: to those people who are always available for support of their blind loved one. And no

doctor, I believe, would refuse to make a diagnosis of eye blindness because a diagnosis is crucial

to get the needed support which society provides to blind people and to also enable the validation

which you and the children, as the family of a blind man, need from other people.

But if your spouse instead suffers from a much more severe disability than eye blindness; if he

suffers from mindblindness, which is a key feature for people with Autism Spectrum Disorder

(ASD, AS), then the reality of the Health and Medical system is somewhat different.

This is my experience with a psychiatrist and highly esteemed specialist in Asperger’s syndrome

and Autism Spectrum Disorders:

*

In 1997 I married Harry after we knew each other for 2 years. There were already weird behaviours,

but I never heard of Asperger’s syndrome or High Functioning Autism. I was in love.

After the wedding the weird behaviors increased rapidly. A friend of ours was worried. He was very

conscious of Harry’s strange conduct. He liked him a lot, but couldn’t understand what was going

on. The behaviours did not fit anything recognisable as people’s general oddities. On the one hand

Harry seemed to be a kind person making great effort for people to like him. On the other hand, our

friend noticed that Harry lacked common sense, treated me unfairly, hurtfully and dishonestly

without showing the slightest regret or remorse. When Harry caused problems and hurt people

around him, it seemed like he didn’t understand the link between cause and effect. Instead he

blamed everybody else, and on rare occasions when faced with his culpability, he either denied it or

switched immediately to victimhood.

Our friend saw how much I suffered. Together we started to search for “something” that could

explain the various cognitive, mental and physical symptoms we noticed. Because of those

symptoms we looked in the neurological field. There it was: Asperger’s syndrome; High

Functioning Autism.

Scary

It was a wake up for me. Asperger’s! No doubt. Flapping hands, no eye contact, lack of empathy,

unable to maintain a reciprocal conversation, lack of impulse control, endless monologues about his

special interests, childishly eager to satisfy his own needs, no striving for mutual understanding, no

responsibility for his own conduct – and at the same time having an impressive knowledge about

topics that interest him.

I was relieved: relieved, because I understood Harry’s behaviour had nothing to do with me. It was

all about a disorder on the Autism Spectrum: an invisible, but pervasive and severe neurological

disorder.

I didn’t say a word to Harry about Asperger’s syndrome. I felt he would not be able to cope with the

truth. Furthermore, I felt intuitively, it could be dangerous for me to tell him. So far, the knowledge

was a help for me to interpret my husband’s intelligence gaps and socially inappropriate, egocentric

behaviour. I used this insight to support Harry as best I could.

A couple of years later, sitting in the kitchen in the evening, Harry was verbally unusually cruel. At

that time I knew all about the Asperger’s arrogance and uncontrollable urge to belittle anyone who

didn’t have his special knowledge and didn’t share his opinions. It was exposed to me almost every

day and I had trained myself not to pay attention because it was too stressful for me. But this time

he was unusually verbally cruel. He did not respond to my requests to stop, but increased the cruel

verbal abuses. He hurt me again and again, and I just knew: I have to tell him. I was exhausted and

despaired at trying to understand and cover up for the man I loved and at the same time being

abused and belittled.

“I have to tell him,” I thought. And I did.

I didn’t even finish the words “Asperger’s syndrome”. All I managed to say was, “Harry, I think,

you possibly have a disorder called Asperger’s syn…”

Smash. He struck me violently. I lay on the kitchen floor and bled. He kept beating me hard. At

every stroke he shouted furiously: “I’ve never hit you, I’ve never hit you. I’ve never hit you”.

I was terrified. He went on and on, I couldn’t move. He did not stop beating me, until I begged:

“It is my fault, pleeease forgive me”.

Should I have gone to the police?

I didn’t. Instead I called our friend; the only person who knew the truth. He talked to Harry, and I

was stunned how Harry spoke with such control and so friendly on the phone as if nothing had

happened. As soon as our friend was on the phone Harry had full control over himself; in a split

second he was able to change from a scary and violent man beating his wife, into a charming

pleaser. It was only her who was hysterical he said cheerfully to our friend. “Everything is OK!”

It was bizarre. How can anyone behave so comfortably right after he has beaten his wife, drawing

her blood?

To me it is a mystery how a person who normally is passive and extremely slow to react: if he

reacts at all to his family’s attempts at interactions, suddenly was able to transform himself into a

vicious assailant, and then a moment later, as soon as our friend came on the line, was immediately

able to transform himself once again: this time into a cheerful “nice guy”. Is that what some people

who advocate for those on the spectrum call “honest, naive and innocent”?

I am deeply grateful that our friend did not let himself be manipulated. Instead he told Harry about

Asperger’s syndrome. Told him his assessment that Harry had an autism spectrum disorder called

Asperger’s syndrome and suggested to him that he be properly diagnosed.

No remorse

Our friend’s support and validation was invaluable to me. But what I couldn’t imagine that

frightening evening in the kitchen was that our friend would turn out to be the one and only person

around us who understood the truth; consistently showing support and validation which helped me

to survive.

Harry never apologized after the violent abuse. He never expressed any remorse. But over the next

few days he was subdued. After a week I told him gently that I had found a private person who

could test him informally just to see whether it was Asperger’s or not. That day I experienced a

miracle: Harry said, “I’ll go and see that man. I’ll prove to you, that you are wrong.”

Harry came back from the test almost singing to himself and in a good mood.

He said, “Well it seems like I have this asp thing,” while laughing to himself. “People with

Asperger’s are highly intelligent!”

I managed to suppress the smile that bubbled up in me. I was familiar with the misleading myth of

“high intelligence”, that some people with Asperger’s autism constantly repeat to each other.

“This man you visited”, I asked. “Is he on the autism spectrum?”

“Yes”, Harry said. “He has Asperger’s syndrome. He is a very nice guy.”

This narrow-minded focus could not be the end of our journey towards an honest and responsible

management of reality. That’s what I thought as I relied on the expert! So I planned for another

miracle. I already had the name of a Scandinavian specialist: a psychiatrist and expert in this area of

neurological disorders. I told Harry that it was a good idea to make an appointment and get an

official diagnosis.

Harry’s response was, “Why? He is a psychiatrist? I’m not mentally ill.”

I replied, “He is ALSO a specialist in this Asperger’s syndrome.”

I couldn’t believe what happened. Harry was willing to contribute to the next miracle: consulting

the specialist and getting a formal diagnosis.

We stipulated an appointment for a tele-conference with the psychiatrist. The day arrived, and with

me beside him, Harry actually phoned this specialist at a prestigious hospital.

“Have a nice day”

This was the precious moment in a long marriage: when my aspie-spouse was actually willing to do

the right thing: namely to clarify the reality and truth about his suspected diagnosis. A clarifying,

which obviously is a prerequisite for being able to handle the challenge in a marriage, where I am

the other half.

I was fully aware of the precious moment. Among the severe characteristics of Asperger’s

syndrome is the mindblindness and lack of acknowledgement of their own disorder. But with the

violent incident still in mind, including my bruises and wounds, and with Harry’s selfunderstanding as a good person, this was the rare moment, where a diagnosed “excuse” for his

behaviour would be easier to swallow for Harry than the idea of being a violent wife-beater.

Harry got the specialist on the phone. He asked Harry some questions on the telephone to get a

picture.

“It sounds a lot like Asperger’s. Can very well be”, the psychiatrist said, explaining that Harry

would have come to his office for a proper clinical diagnosis, which Harry declared he was willing

to do.

Then the psychiatrist asked:

“Why do you want to get diagnosed? Why do you need it?”

Harry replied, “I don’t know. It’s my wife…”

Psychiatrist: “Do you have any problems on the job or with your family life?”

Harry lied, “No, I have no problems.”

Psychiatrist: “Well, if you don’t have any problems possibly having Asperger’s syndrome, then I see

no reason to spend more time on this. You just go on with your life! Have a nice day!”

I was paralyzed. I couldn’t breathe. This could not be happening.

Harry turned to me and said, “The doctor says there is no reason for seeing him! You just ask him!”

Harry handed me the phone.

“But,” I stammered into the handset.

No reply. Gone was the expert. Gone was the precious moment.

The betrayal

A month later, Harry denied he ever had been to the first private practitioner and denied he got an

informal diagnosis. He denied the tele-conference with the psychiatrist. He denied everything.

In despair I contacted the psychiatrist for a final attempt. I told him about the denial. Tried to make

him understand that a correct diagnosis was important for our life, for other people’s wellbeing and

important for the public health care system which risks committing medical errors to Harry’s

detriment, as he frequently consulted physicians about his various health problems.

The psychiatrist didn’t care.

The primary betrayal by a spouse on the autism spectrum is horrific. But the secondary betrayal by

an expert, who is supposed to help and is even paid by the tax-payers, is worse.

I had lost. Respect for the medical truth was lost. The professional’s ethical responsibility, that I as

a matter of course expected, was non-existent. Instead, this health authority representative sent my

nice, but mind-blind and neurological disordered husband away with the false perception that his

conduct did not give rise to any problems! Just as if an ophthalmologist had encouraged an eyeblind person to move around in traffic as he pleases, because: You don’t have any problems! It’s just

all the others out there in the traffic, who see the problems!

I sank into despair and loneliness. Life went on. The psychiatrist went on sitting in his office

writing forewords about ASD, while the problems around Harry caused by his severe disorder, piled

up.

I spent all my spare time helping my husband legally solve dozens of complaints against him

coming from his colleagues and from the parish council, where he was a vicar. In my head the

psychiatrist’s untruthfully answered question resounded: “Do you have any problems on the job?”

Adults with Asperger’s/High Functioning Autism always have problems on the job and in family

life. Hfa sufferers are dealing with a pervasive, severe disorder, that by definition affects all areas of

human relations, and which by definition (lacking Theory of Own Mind/insight) implies lack of

self-awareness by the person, who has the disorder. No responsible and decent expert would ever

base his assessment on a brief telephone statement from a mindblind person.

Absence of ethics

This expert did. But what the expert did not do was to ask me (and Harry) the most fundamental

questions, that anyone with common sense and a basic knowledge about Aspergers syndrome

knows are essential, when you are dealing with a possible Autism Spectrum Disorder:

Does Harry have children? Are there siblings on the autism spectrum? Problems with impulse

control? Beaten his spouse? Pushed her violently down the stairs? Has Harry a Firearms Licence?

Other diagnoses, e.g. Tourette’s syndrome or epilepsy? Suffering from legal drug abuse? Anxiety?

Depression? Eating disorders? Gut problems? Skin problems? Ludomania? Consulting medical

specialists because of sensory problems with sound and light? Violating other people with

exhibitionistic behaviour?

The great majority of these questions can in this case be answered with a “Yes”, which in turn

places a clear responsibility on the health authorities who accordingly would have relieved the

spouse and possible kids from some of the traumas and continuous stress and fear.

I was never relieved for anything. Complaints from colleagues and the parish council continued and

continued. Some people in the ecclesiastical bureaucracy did everything to get Harry fired. There

were times where Harry had long periods of sick leave. For years I found myself in a state of

despair, stress and depression. I managed to protect Harry from their “projectiles” and get the

malicious complaints rejected as unjustified. At the same time it was obvious to me, that these

people understood “something” was wrong. It was just that they had no idea what this “something”

was. Instead, they fabricated the most vicious lies and accusations. I was the one who suffered. I

couldn’t bear to witness the evil that was unleashed against my husband. At the same time I felt

abused by Harry because he refused to cooperate and deal with the truth in terms of his diagnosis.

Harry was 54 years old when the precious moment occurred – and was lost, thanks to an

irresponsible expert. The words “Asperger’s syndrome” are still taboo. Harry’s denial of that which

a competent expert would have removed by virtue of his authority, keeps life on eggshells.

Stop explaining away the truth

I have no illusions that life would have been seamless if Harry at that time had been met by a

responsible and dutiful health care person. But I know for sure that dealing with ASD requires more

from a professional than the lazy question, “Do you have any problems?”

Today, more than ten years later, I have had contact with hundreds of neurotypical (NT) spouses in

Scandinavia and many more from around the world. What shocks me is that so many NT spouses

experience the same kind of dismissal from autism experts as I experienced at that time. Can it be

true, that only a few pioneering medical experts around the world have a vision of the whole

family’s well-being, when an adult in the family suffers from High Functioning Autism/Asperger’s

syndrome?

My request to all autism experts is this: Stop explaining away the reality of Asperger’s/High

Functioning Autism. It is self-evident that autism- as other disorders – is nobody’s fault. But when

the scientifically proven devastating effects on children and families of adults on the Autism

Spectrum are ignored by experts, this part of the problem’s complexity becomes your fault. As

experts and medical professionals you have an ethical responsibility. Use your expertise to make

accurate diagnoses for adults and reluctant AS/Hfa then accurately inform the public how AS/Hfa

affects spouses and families of people on the spectrum.

It helps no one, least of all persons with AS/Hfa and their caregivers inside the families, when the

severe effects of their disorder are wrapped away in cotton candy.

© Sofia Morgan

Scandinavia

May 24, 2014

PDF:

Some observations of my own about pathological demand avoidance and other puzzles within the context of Asperger’s

William tells a friend that his wife has taken his iMac and shipped it off as a donation to a developing country. He adds that she’s found another iMac on the street. Can the friend help him set it up?

Finding an iMac on the street may sound odd, but William and his wife often find discarded yet very useful things on the street. Why not an iMac?

This “new” iMac turns out to be William’s own iMac. His wife had moved it by 10 cm and rotated it by 90 degrees.

(Do you see the autonomy angle?)

Highly concerned about this and other issues, the friend confronts him with this later. He suddenly flies into a rage, grabs her and throws her onto the floor. It’s not as extreme as with Harry, not at all, but the switch to calm afterward – as if absolutely nothing has happened – is confusing.

Online, other autistic people have said that what allistic people call pathological demand avoidance is about AUTONOMY. This would be a good example.

It’s also about pain and betrayal. It’s about his second wife.

Does moving the iMac represent violating his boundaries? Boundaries work differently for autistic people, I’ve noticed. They often don’t see yours at all. I think that’s because they are so driven by feelings and prone to acting on them. Boundaries don’t feature in that.

William’s first wife divorces him when he’s about to reach pension age. William may see a relationship and being married as a sign of his value and normalcy. Some time later, photos of a woman who is about 40 years younger are on all the walls of his new apartment. There are discrepancies in this woman’s stories, at least the way William tells them. It’s hard to assess what is true and what isn’t.

William marries this woman.

“Surprise!” she announces one day, as told by him to a friend. She’s pregnant. He’s the father. Only, he’s not – and he knows it. She keeps the boy with her at all times, which makes it very challenging, but he eventually manages to get a sample that he can send off for paternity testing. Sure enough, he’s not the father. He doesn’t tell his wife. He tells the friend and adds: “I simply really like her.”

(Does he feel vindicated or validated by being married to her?)

There is an odd duality in how he both resents his second wife for her betrayal and blind assumption that he’s really stupid (which he isn’t) and at the same time allows her to dictate his life to a large degree.

(The second child wasn’t his either, of course.)

Here you see how this sense of autonomy plays a role again. William doesn’t want to be told that he’s being used. He doesn’t want to admit it. He plays along because that way he can tell himself that everything is alright and that he’s in control. She clearly doesn’t even want to be around him as she goes to stay with “girlfriends” when he’s home. He comes up with excuse after excuse as to why his wife does certain things.

She plays him.

She abuses his loyalty and uses the children to manipulate him.

He feels overwhelmed. He senses that his autonomy is being eroded. That’s an accurate assessment.

He starts to rebel. And he’s under a lot of stress. Except, he doesn’t realise it. He increasingly often gets lost in traffic and it really worries him. He tells the friend.

William’s profession includes maps and geography. One evening, the friend sitting next to him, he drives the wrong way a few times and dismisses her, treats her as if she doesn’t know anything about anything, but this is not about her.

This too is about autonomy.

Then, suddenly, almost as if to demonstrate what is really going on, at the very last minute – no, second – he yanks the wheel to the left at some point and very deliberately drives into the clearly marked wrong direction.

This is not about age-related cognitive decline. This is about wanting his autonomy back. He wants to put his foot down, but he doesn’t know how and doesn’t want to end up “abandoned” again either. (Btw, his first wife seems to know this too and tries to support him in her own way.)

Confusingly, there also was age-related or stress-related memory decline.

William then turns his attention to the friend. Maybe she can rescue him, in a way that preserves or restores his sense of autonomy. He doesn’t know any other way. He needs someone to be on his side. He needs loyalty.

First he tells the friend that she can sleep in his wife’s bed when she’s not there. (She is not only “staying with a girlfriend” often, she also travels out of the country frequently.) Is that really about autistic people not understanding boundaries and conventions? He tells her that the others will simply have to put up with the friend as it’s HIS house. Here we see the need for autonomy again, perhaps.

He starts plopping down much too close to her and far too enthusiastically, getting up just as quickly again. He gives her a somewhat trashy book to read and take with her in which a man is already looking at a woman’s – a stranger’s – nipples from a distance, in the night, in the first few pages. The friend (who had noticed two years before that he was a little too interested in the fact that she had a black lace bra – which she had tried to hide from him, btw – and sensed too much interest of a particular kind, had already deliberately tried to act as genderless as possible so as not to create the wrong impression or complications) realises that she has to put that book away adapter not take it with her.

The next thing that happens is that she looks up one day and finds him standing there, staring at her intently, making really weird wiping motions across his mouth. It looks really bizarre. She’s bewildered. What on earth is he doing?

Here we have an example of autistic people having trouble reading allistic people. He must once have been told that when a woman wears lipstick, it signifies interest, particularly if she doesn’t wipe it off. He moves in. She gets up before things get out of hand.

(Had he expected her to be scheming, perhaps, just like his second wife? Had he misjudged that?)

(Boundaries. From the bra to confidential client documentation on a desk to opening a neighbour’s apartment’s door without knocking and simply stepping inside just because the door wasn’t locked for a moment and there was some kind of smell.)

Skip forward.

He mopes like a child, but it’s over what he seems to perceive as her lack of loyalty. He wasn’t looking for a relationship. He was looking for a way out, someone to defend him and free him from the manipulative second wife, keep him safe.

This becomes clear in how he responds to it when she says she would like a glass of the good white wine that he received as a Christmas gift, but that he doesn’t like instead of the cheap, not-so-great anonymous red wine that he prefers. It’s not about the wine. It’s about not siding with him, in his eyes.

Olive oil, milk chocolate, it’s suddenly poison to him. It’s as if anything she eats or suggests or likes is now toxic or evil in some way, even if he used to like it before. That’s about autonomy, too, in a way. It’s rebellion. Protest. He also comments on the friend’s underwear, suggests that it resembles that of his wife’s adult son (from yet another relationship). That is just anger or resentment over feeling rejected. He does other things too to let her know that he feels hurt and let down by her, almost as if he wants to punish her for being such an awful person.

Of his second wife’s adult son, he speaks nothing but good but the things he says about that young man don’t seem to match reality. The only thing that seems to be accurate is that he works at a supermarket part-time. There’s also the fact that this young man goes abroad about once a month, sometimes for weeks.

The friend eventually wonders if the man may actually be getting into or be supporting some kind of people-trafficking scheme without him realising it.

When she confronts him, when she’s still clueless as to what is really going on, and suggests that he may have caught a virus abroad which is affecting his brain and urges him to have himself tested for something like that, he pushes back. When she confronts him again a few months later, very uncomfortable with what is going on, he suddenly flies into a rage and grabs her, then throws her to the floor, after which he acts as if nothing at all has just happened.

William feels betrayed by the friend.

He expected her to understand.

She can hear that he sometimes talks about her on the phone but denies it when she asks him who he’s taking with. It’s happened before. He probably talks about her behind her back, too, and probably in a similar manner as what he said about his second wife and the iMac. It worries her.

He is not interested in what the friend wants and says about what she doesn’t want. It doesn’t fit into his views.

His second wife (who’s meanwhile filed for divorce as soon as she got what she was really after – which isn’t important within this context) senses this and starts working him again.

At least they act united and are forming a front again, which is good, the friend thinks. The friend still worries, realising that there is nothing she can do about any of this. She’s in a complicated situation herself and not in a position to support him.

This is so complicated as people with Asperger’s tend to misrepresent – label – or misread the reality around them anyway. How can she know what is real and what isn’t?

Thankfully, others seem to start to become aware that perhaps not all is entirely well. A neighbour who William sees as a friendly and helpful soul is actually rather suspicious of the large number of strangers that go into William’s apartment.

She assumes and hopes she’s wrong, but she’s really pleased – somewhat reassured – when a social worker type stops by in relation to a pregnancy but asks markedly pointed questions as to who everyone is and what they are doing there.

Autonomy is a double-edged sword. Confusion and discrepancies between what an autistic person believes or wants to believe versus what others say may result in a type of rebellion that the autistic person experiences as striving for autonomy but that others may see as overwhelm and avoidance.

It’s complicated. It requires patience and a non-judging attitude

I don’t have all the answers.